Zebrafish Embryo Pick and Plate

Oregon State University

College of Agricultural Sciences

Department of Environmental and Molecular Toxicology

Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory

Summary

Timeline

Started

Joined SARL Engineering

Project Started

Initial Requirements Given

PCB Released: Driver Board

Revision: 1.0.0

PCB Released: Lighting Board

Revision: 1.0.0

PCB Released: Driver Board

Revision: 2.0.0

PCB Released: Lighting Board

Revision: 2.0.0

Project Finished

Delivered Units to Lab

Finished

Left SARL Engineering

Key Takeaways

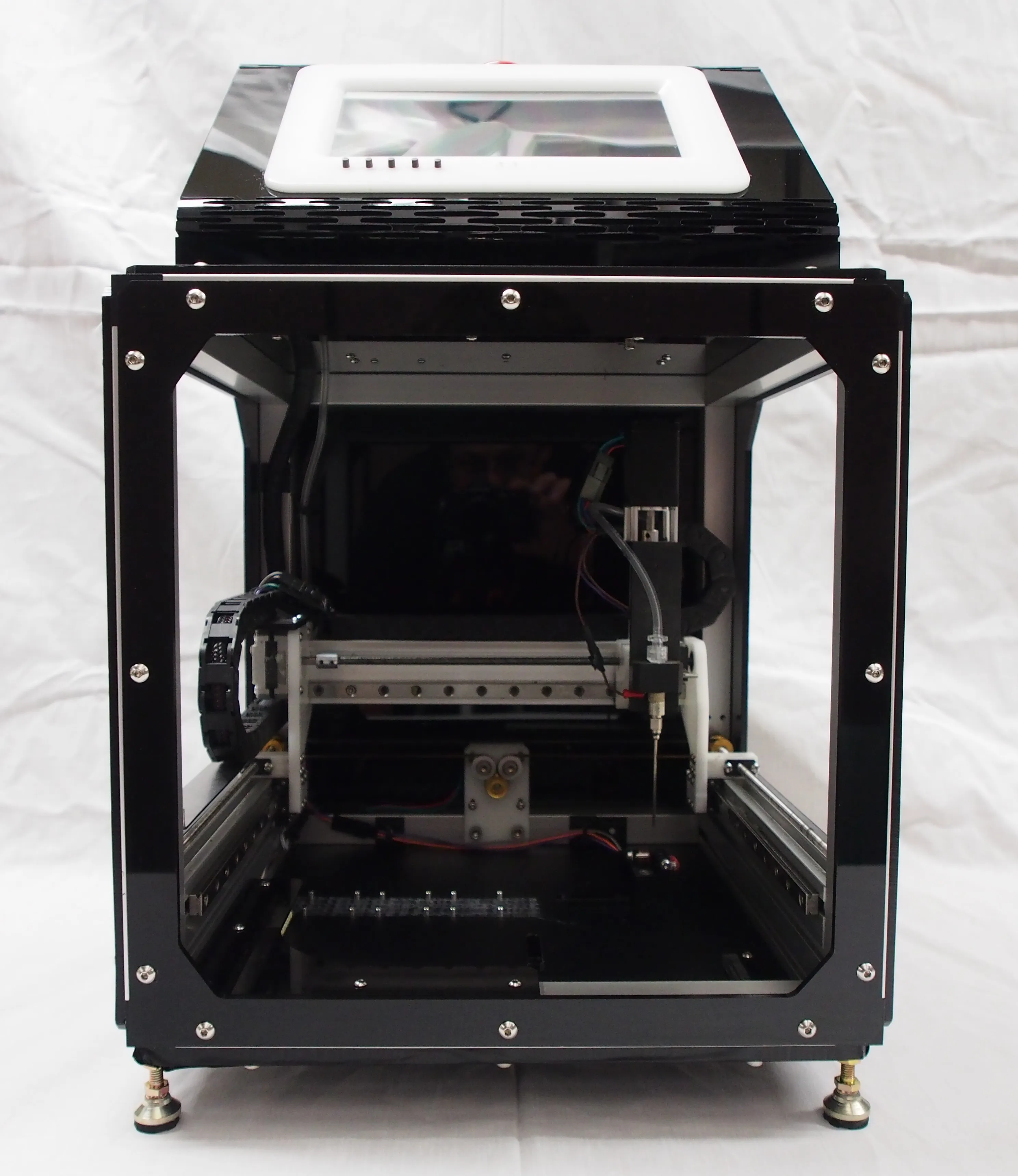

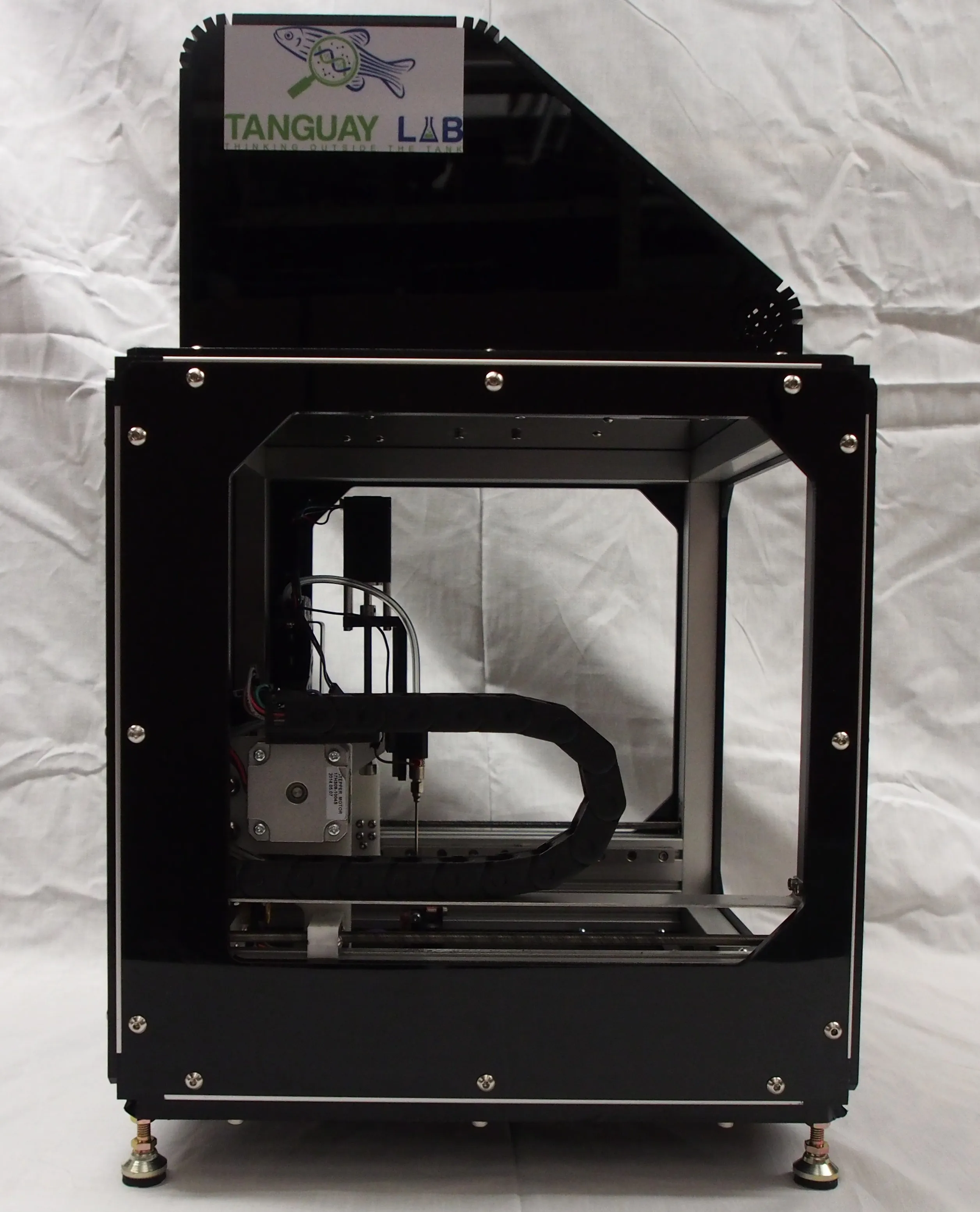

- Delivered a design, and multiple built units, of a custom embryo pick-and-plate machine

- Reduced cost from ~$150,000 for previous generation to ~$10,000

- Reduced the size from 4.5'x4.5'x8' for previous generation to 1'x1'x1.5'

Relevant Skills

Software & Environments

- Version Control

- Git

- Programming

- Languages

- Python 2

- Bash Shell Scripting

- Low-Level Embedded C/C++ (Atmel Studio)

- Frameworks

- OpenCV

- Qt

- Languages

- Operating Systems

- Linux

- Debian

- Microsoft Windows

- Linux

Electrical

- Schematic & PCB Design

- Software

- Altium Designer

- Mentor Graphics PADS

- Manufacturing

- Gerber Export

- BOM Management

- In-House Assembly

- Software

- Electrical Diagnostics

- Multimeters

- Electronic Loads

- Oscilloscopes

- Harnessing Fabrication

- DC Low-Power & Signal

Mechanical

- Fabrication

- CNC

- Hand Tools

Details

For some quick context on why such a machine was even needed, the

Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Lab performs toxicology research using

Zebrafish. This means tha the lab is also a breeding facility,

generating a few thousand eggs a day, which need to be processed and

isolated prior to being introduced to experimental conditions. At one

point in time, these processes were done by hand, with all researchers

spending a significant portion of their day simply prepping the embryos.

Later on, they hired a contractor to design an automated solution to the

isolation problem, and while they delivered, the units were industrial

overkill, using massive SCARA arms and enclosures

to pick up embryos which were roughly half a millimeter in diameter. They

were also very expensive, costing around $150k per machine, and the lab had

four installed. Thus, the engineering team was tasked with cost and size reducing

them so that more could fit in the same space and throughput could be higher.

SCARA

Selective Compliance Assembly Robot Arm

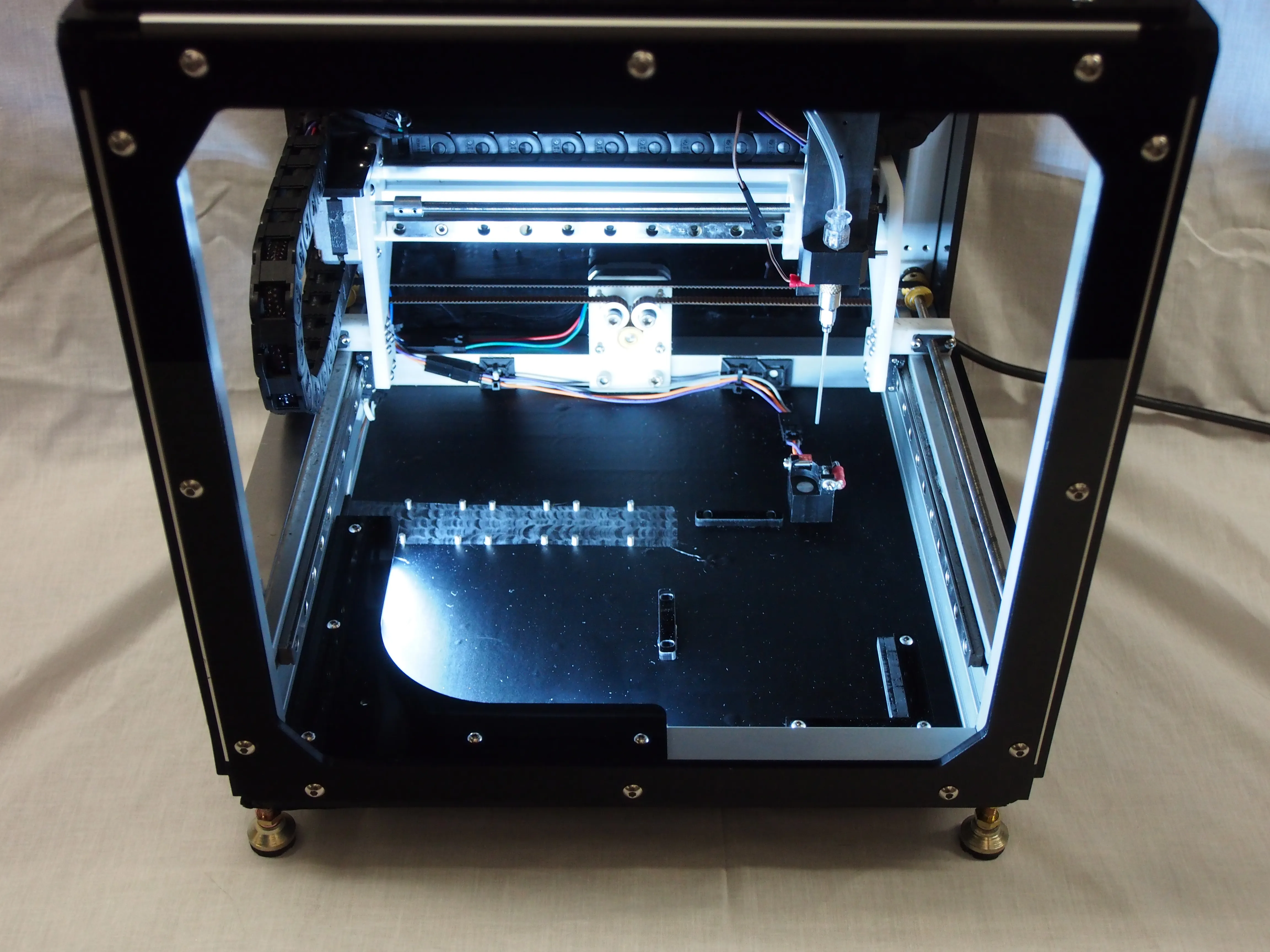

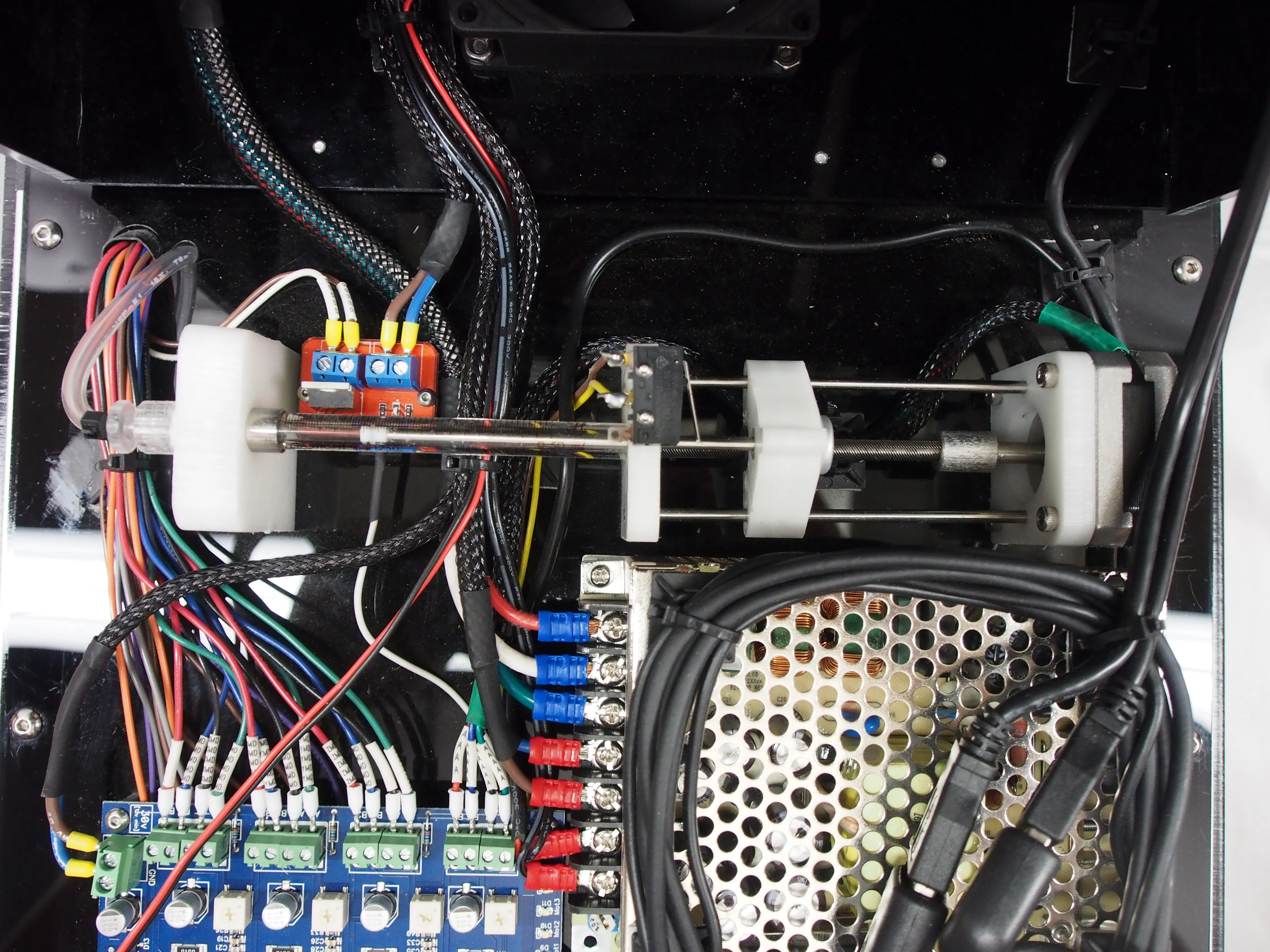

My coworker, Dylan Thrush, and I got to work. He focussed on the mechanical side, while I worked

on electrical and software. I had recently been learning PCB design

after becoming more familiar with it through the OSU robotics club, and

decided that a good place to start would be to create a motion

controller. Dylan and I had already landed on a simple stepper-motor

based system to more than meet the needs of a task like this, and both

of us already had experience with stepper-based CNC machines, making it

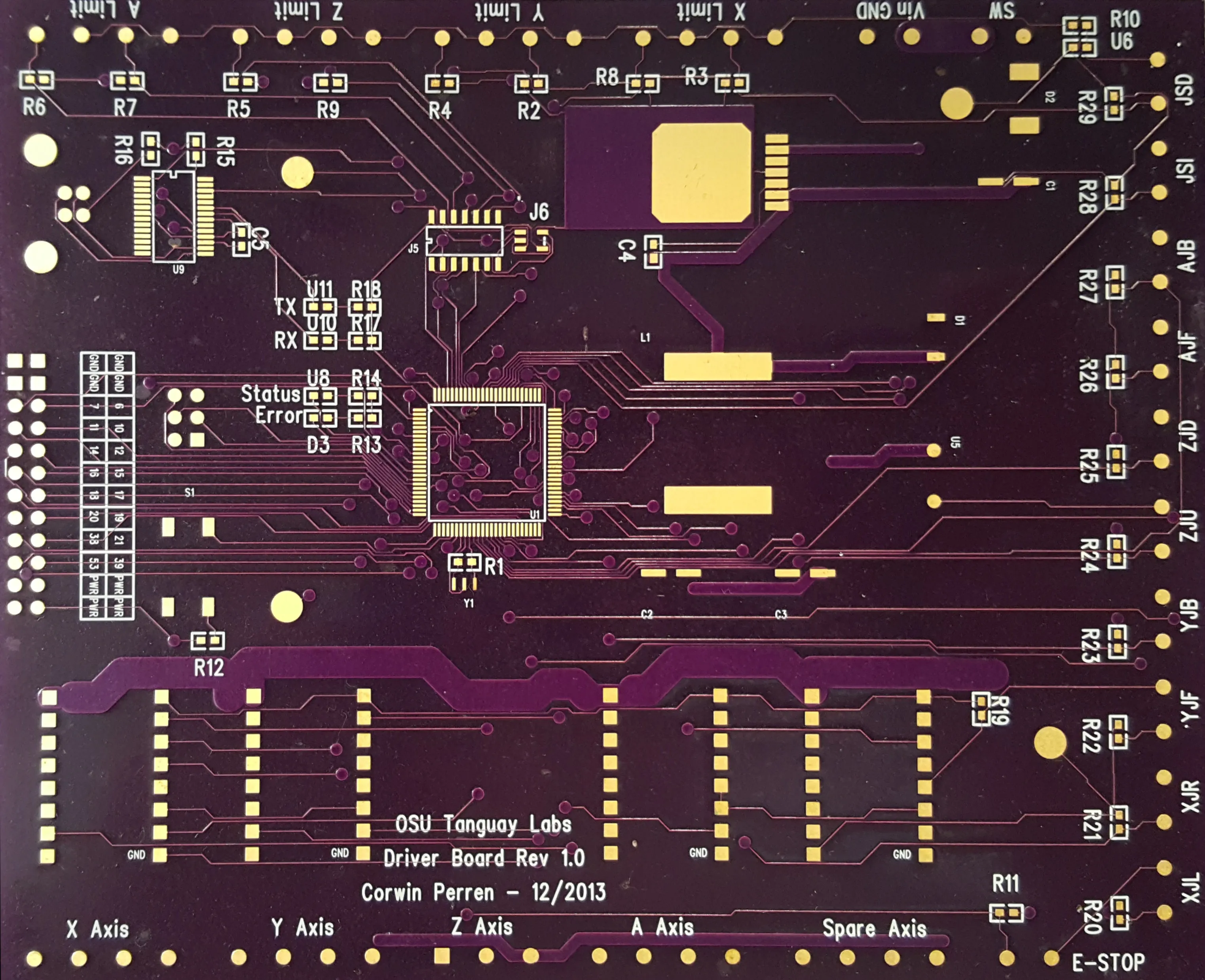

a great jumpoff point. My first PCB was unfortunately a massive failure,

because while I did include a quad stepper motor driver,

microcontroller, general purpose I/O, and usb to serial interface, I

failed to export the gerbers correctly. This resulted in a PCB with no

drills, making it completely useless (outside of a good learning

experience)! It was also just a poor layout overall, which isn't

surprising considering it was my first ever PCB design. If you want to

see this embarrassing result, check out the PCB section at the end of

this page!

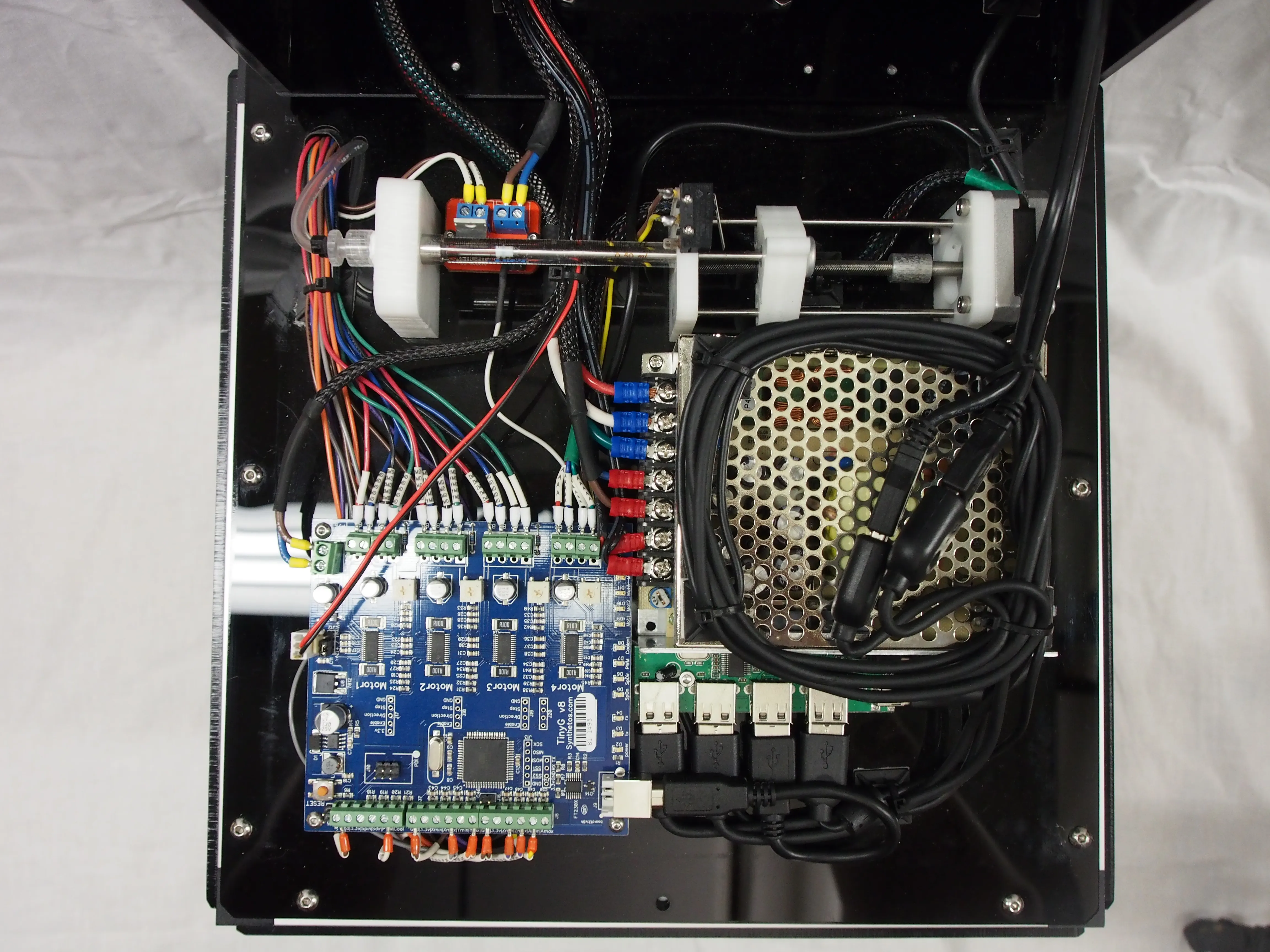

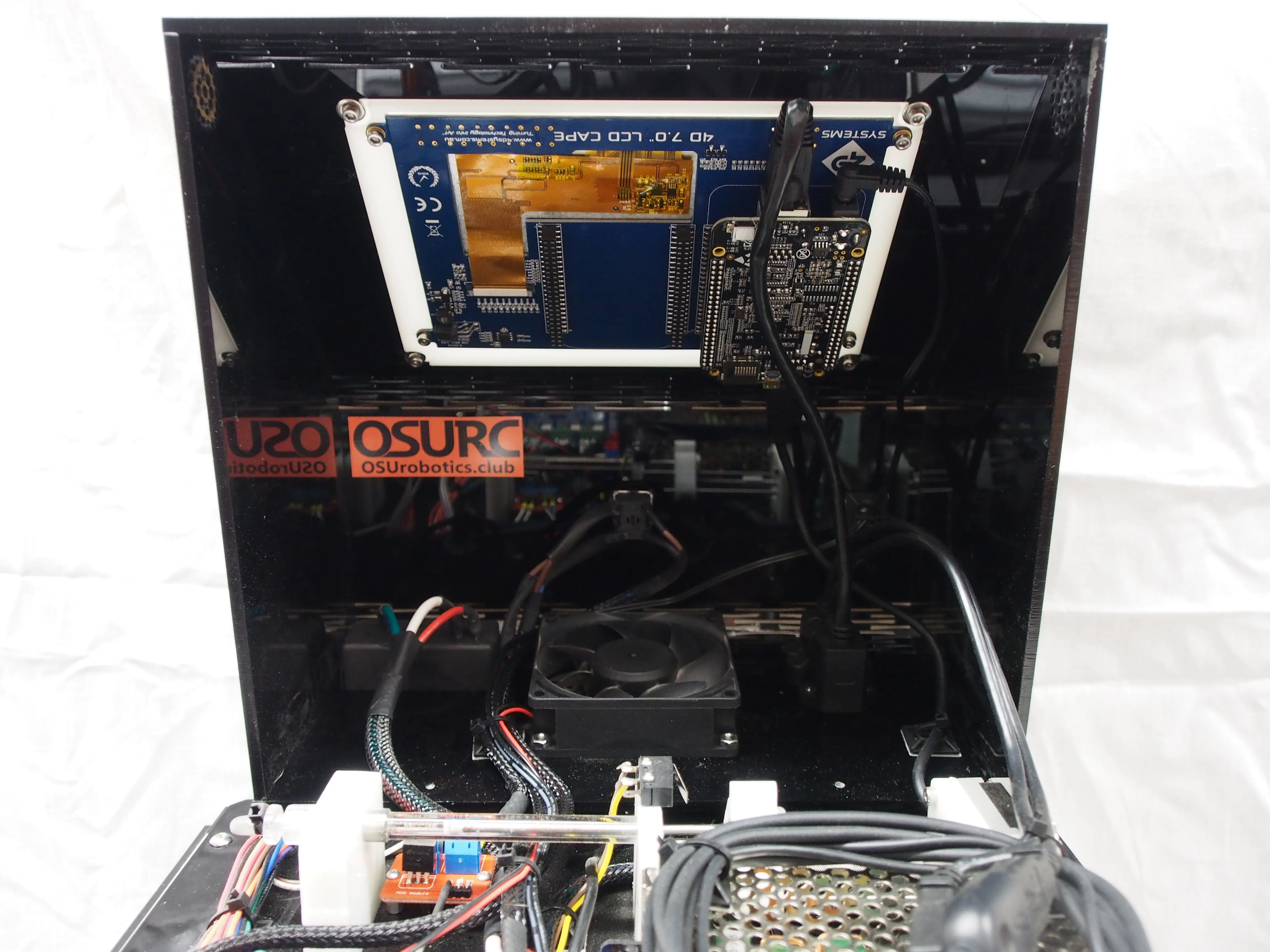

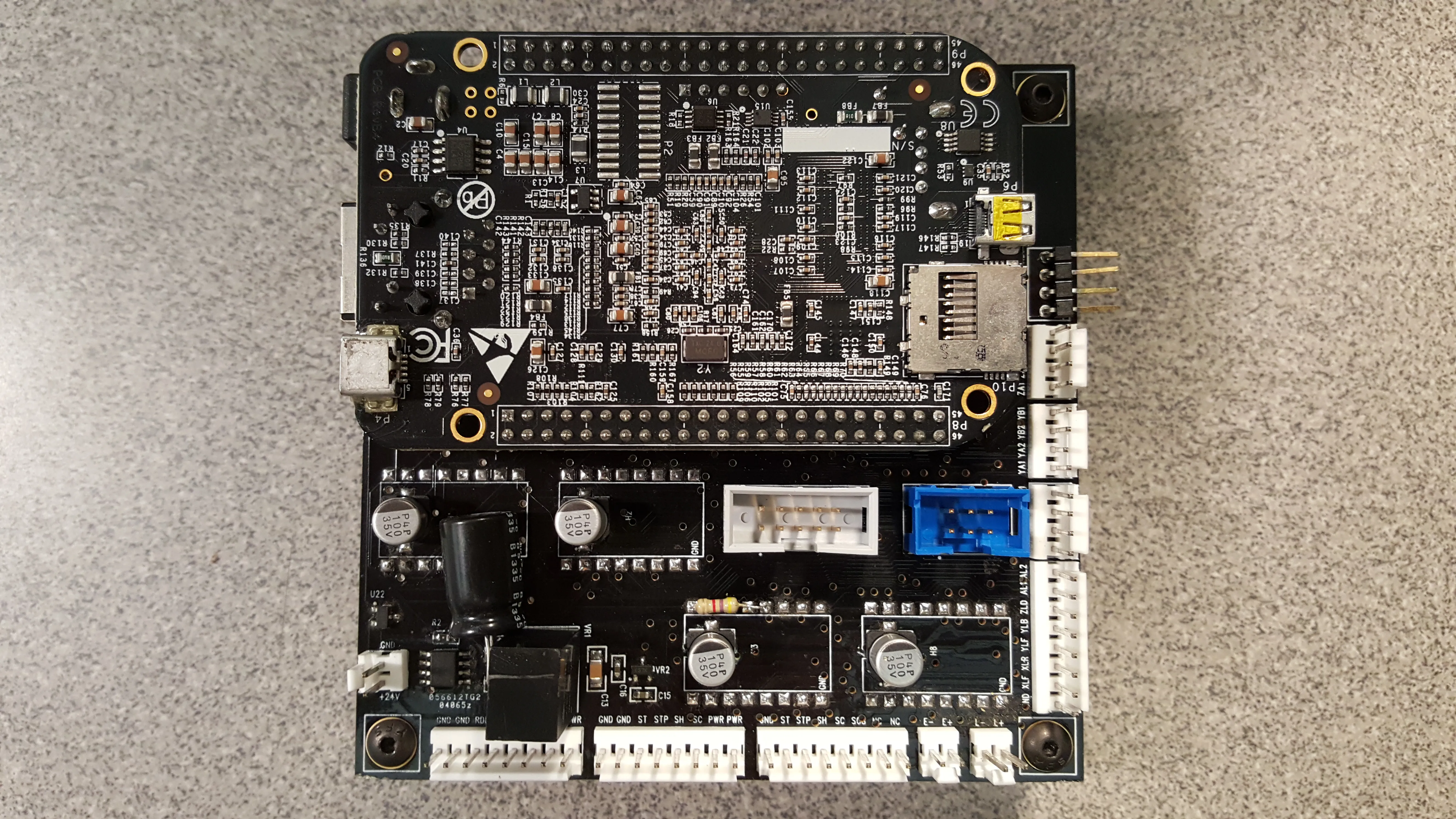

For the second revision, we'd made some progress in other places, but

most importantly had decided that we would use a Beaglebone Black single-board-computer to run the whole system. In an effort to simplify

the assembly, I decided that the next revision would include headers to directly

mount the Beaglebone to the unit, providing power and a serial interface over

those pins. This version actually worked as expected, with only a few very

minor bodges to the microcontroller's crystal, and some bulk capacitance on

the power input. Since things were working, I began writing embedded C to

control motion through some higher-level interfaces. Not long into this process,

I realized I might have bitten off more than I could chew. Not only was I

having to learn the deep ins and outs of microcontroller programming, kinematics,

and serial interfaces, but I would still have to greatly improve my Python

skills, learn to create graphical user interfaces, and figure out how to detect

embryos using a camera and computer vision. While I was sad to scrap this,

we decided to fall back on a motion controller called TinyG, which would simply require gcode to be sent over serial to function.

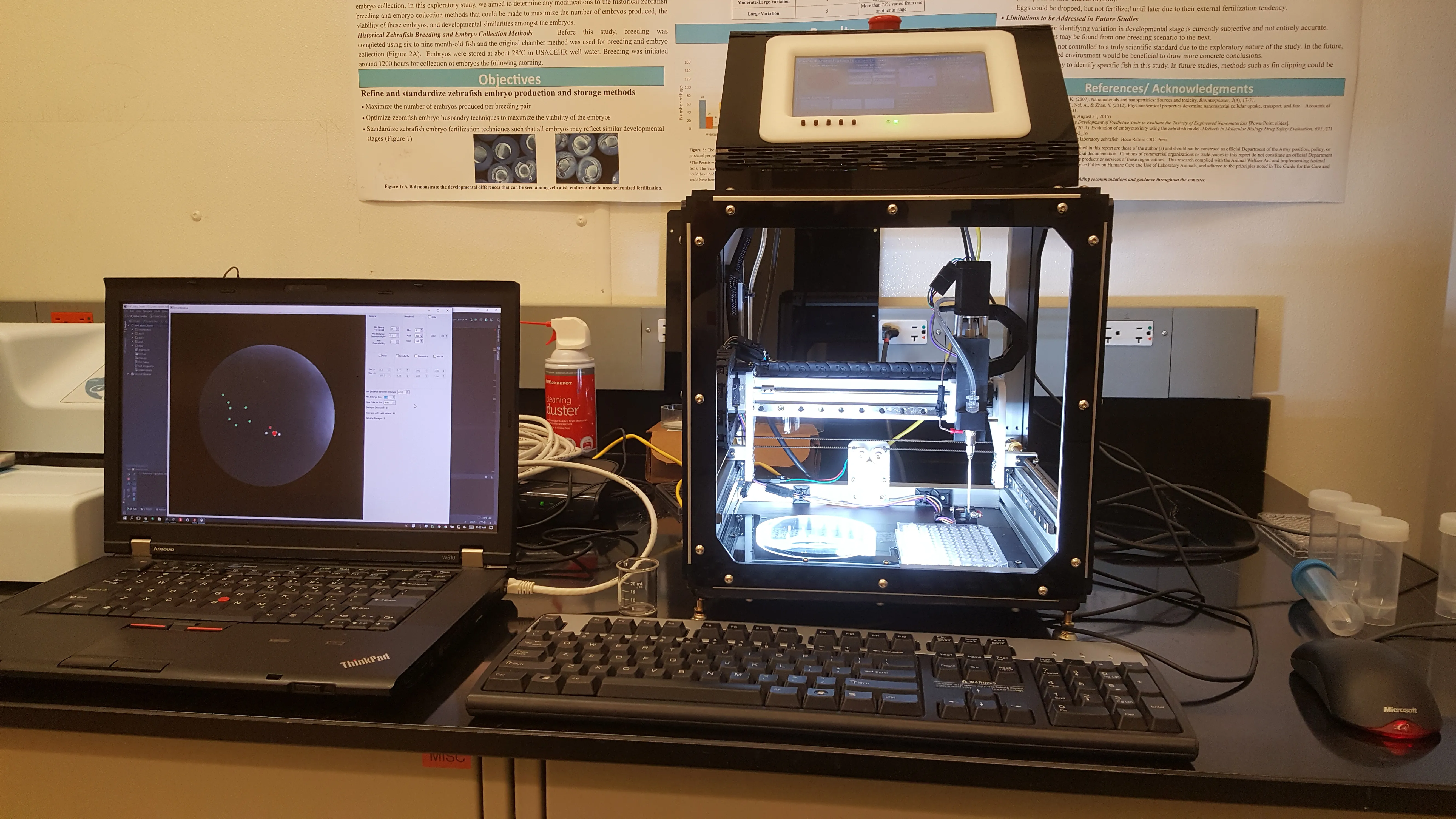

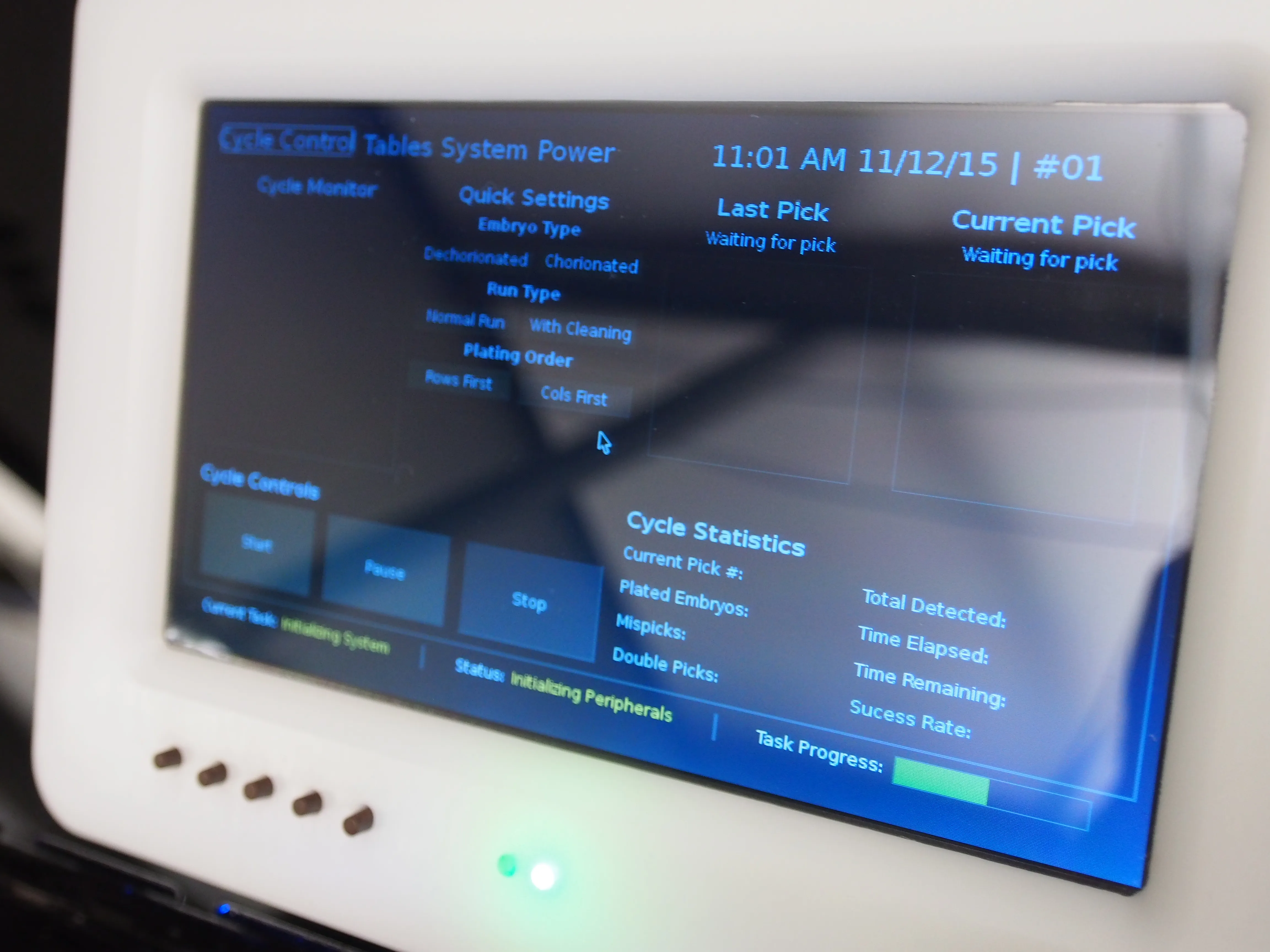

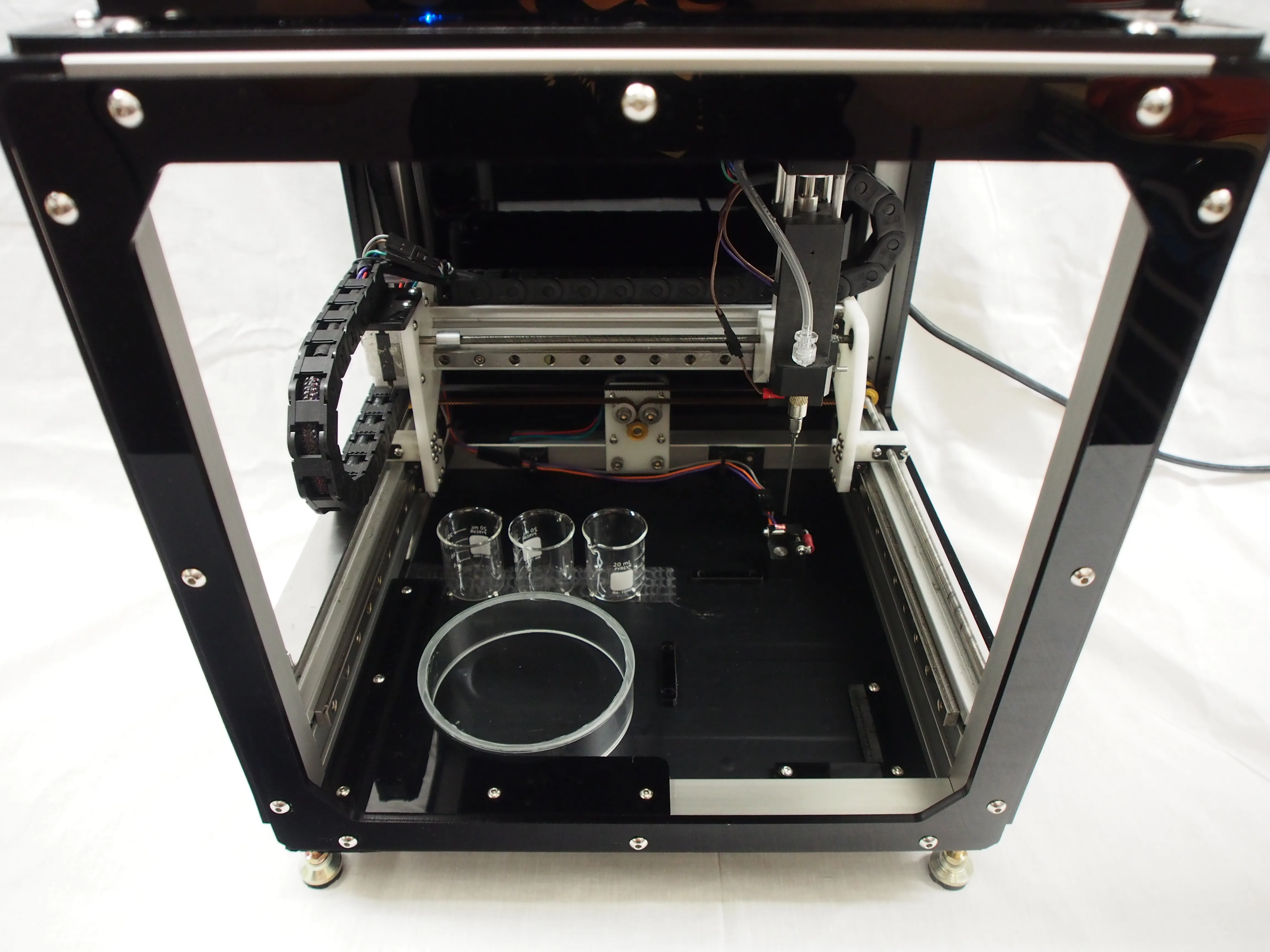

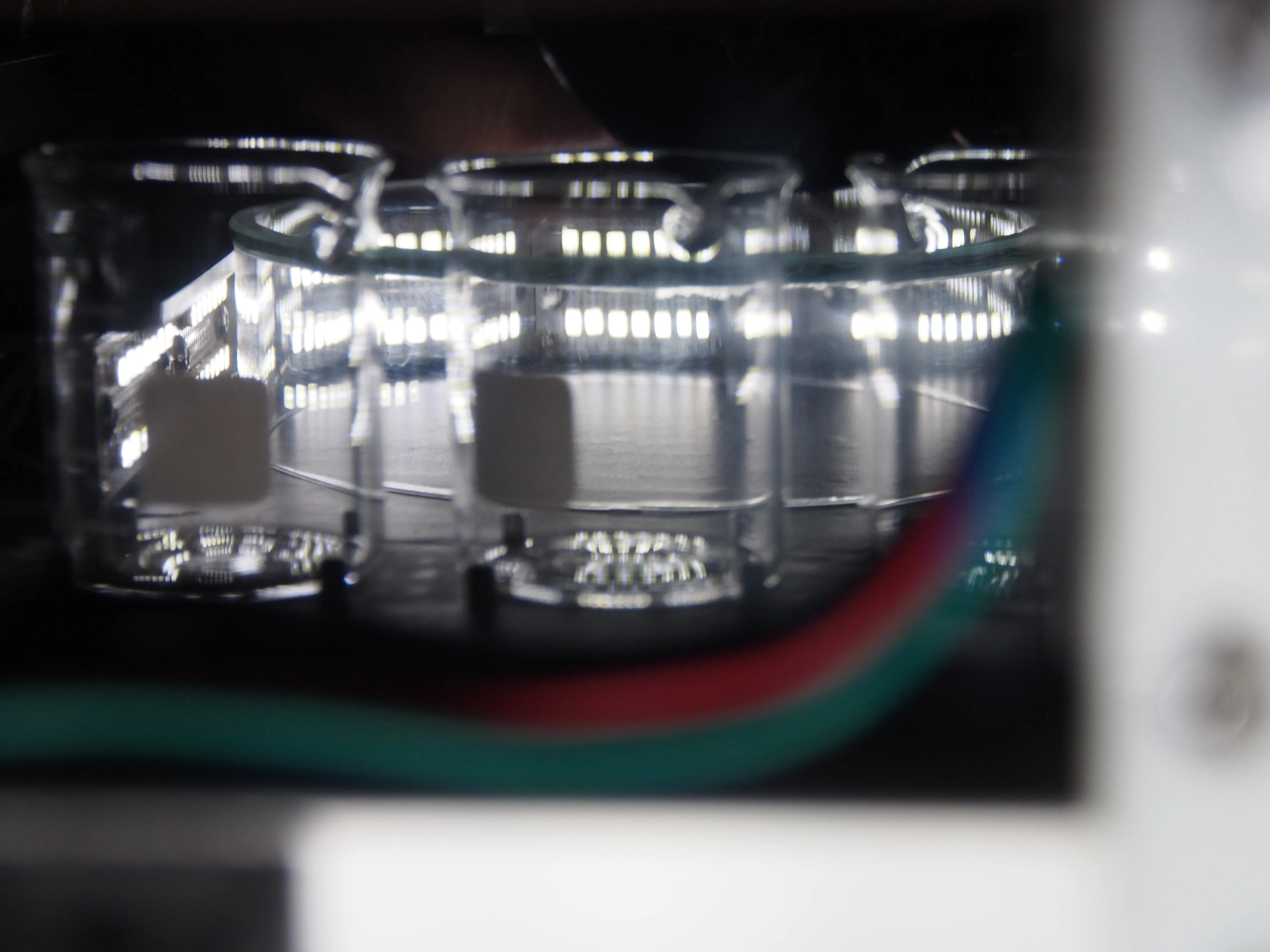

Dylan built up a mechanical testbed, which we could mount a camera to,

and I began to focus on embryo detection. I was relatively new to

Python, but quickly found the Qt framework for building decent-looking

interfaces, and OpenCV for providing generic detection capabilities via

webcams. Over the next few years (remember, we were students doing this

part time, and working on other projects simultaneously), I eventually

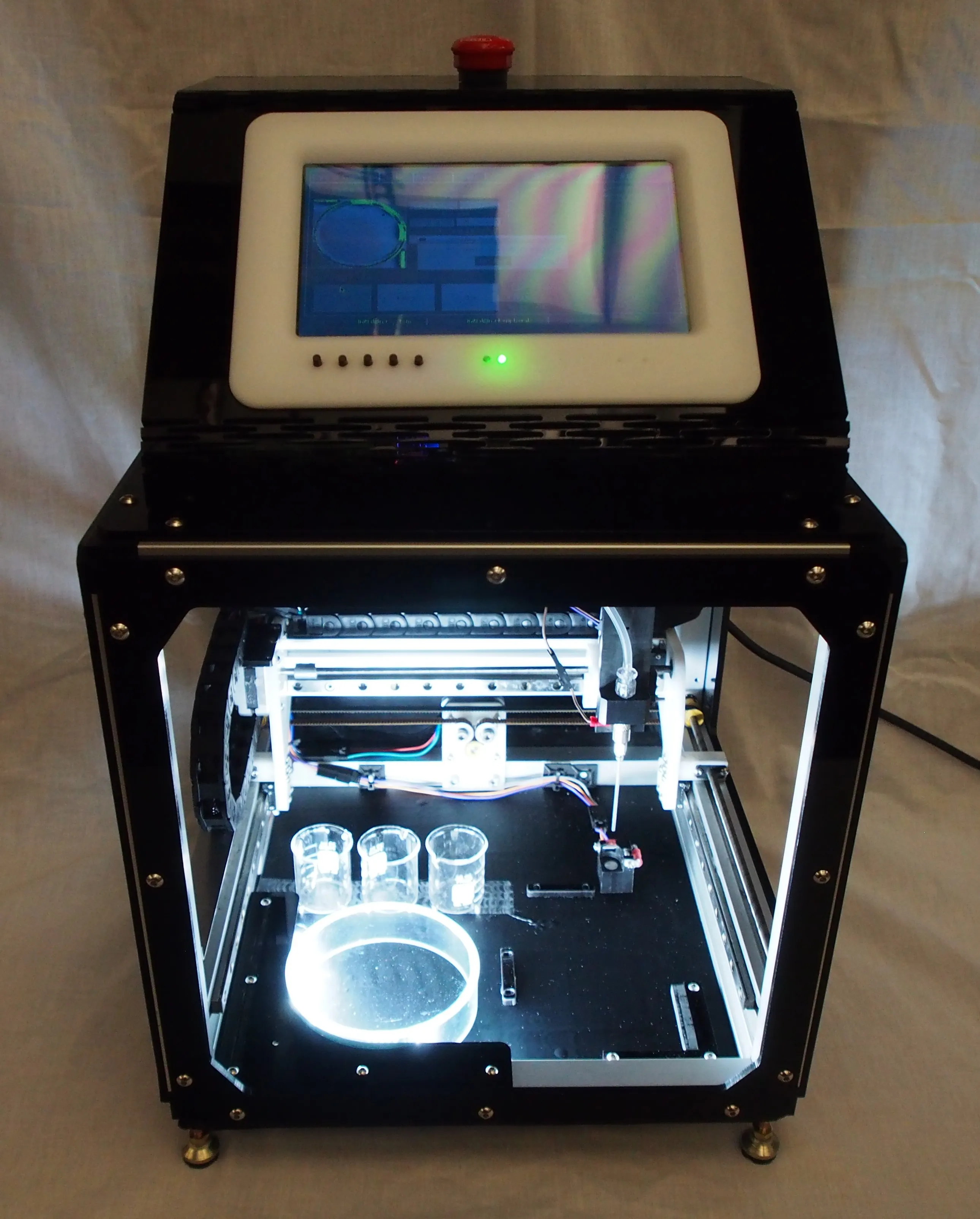

created a fairly comprehensive user interface that would allow

researchers to tune detection and motion parameters on-the-fly. This was

shown on a touchscreen that the beaglebone plugged into, making it quite

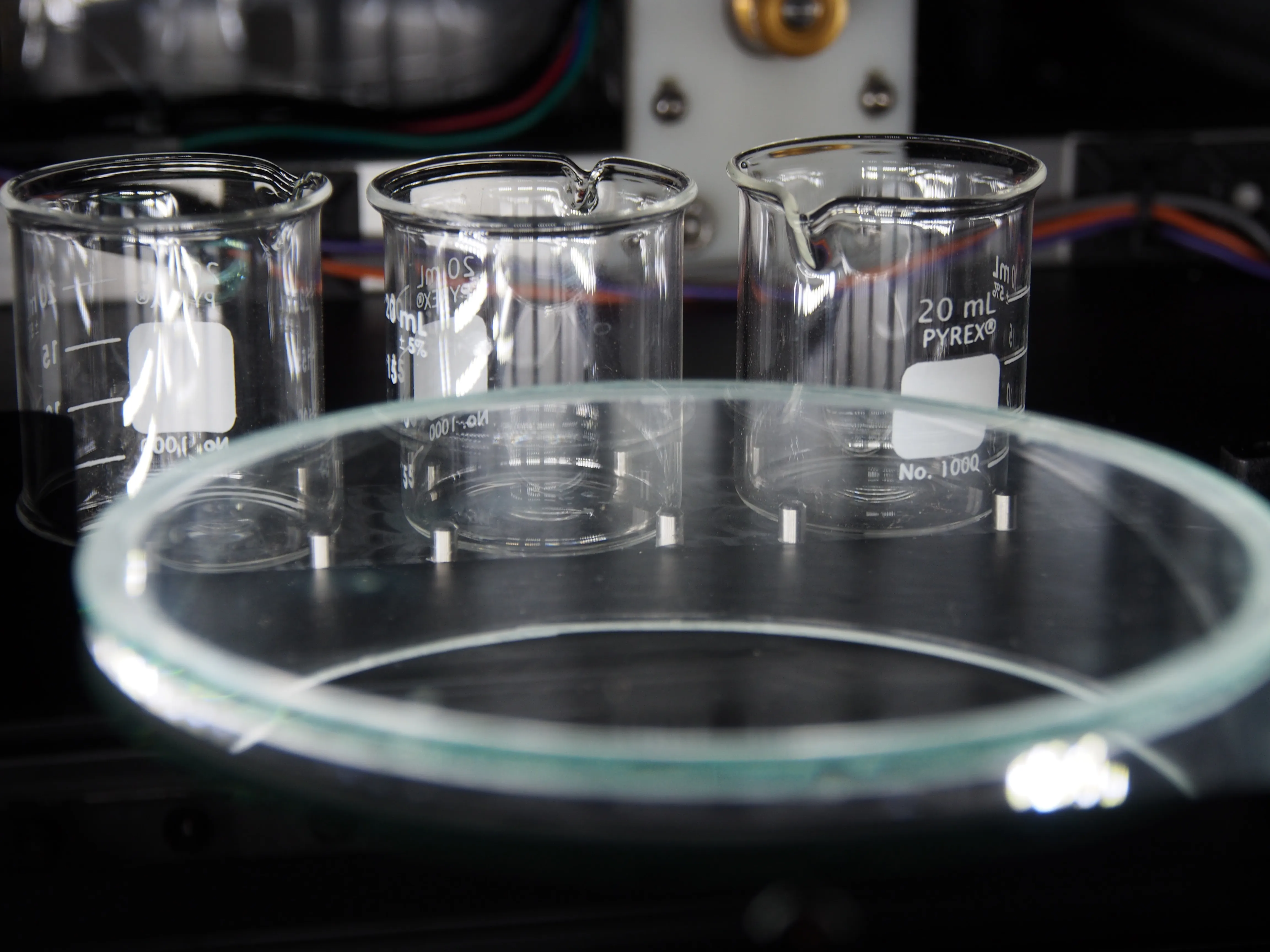

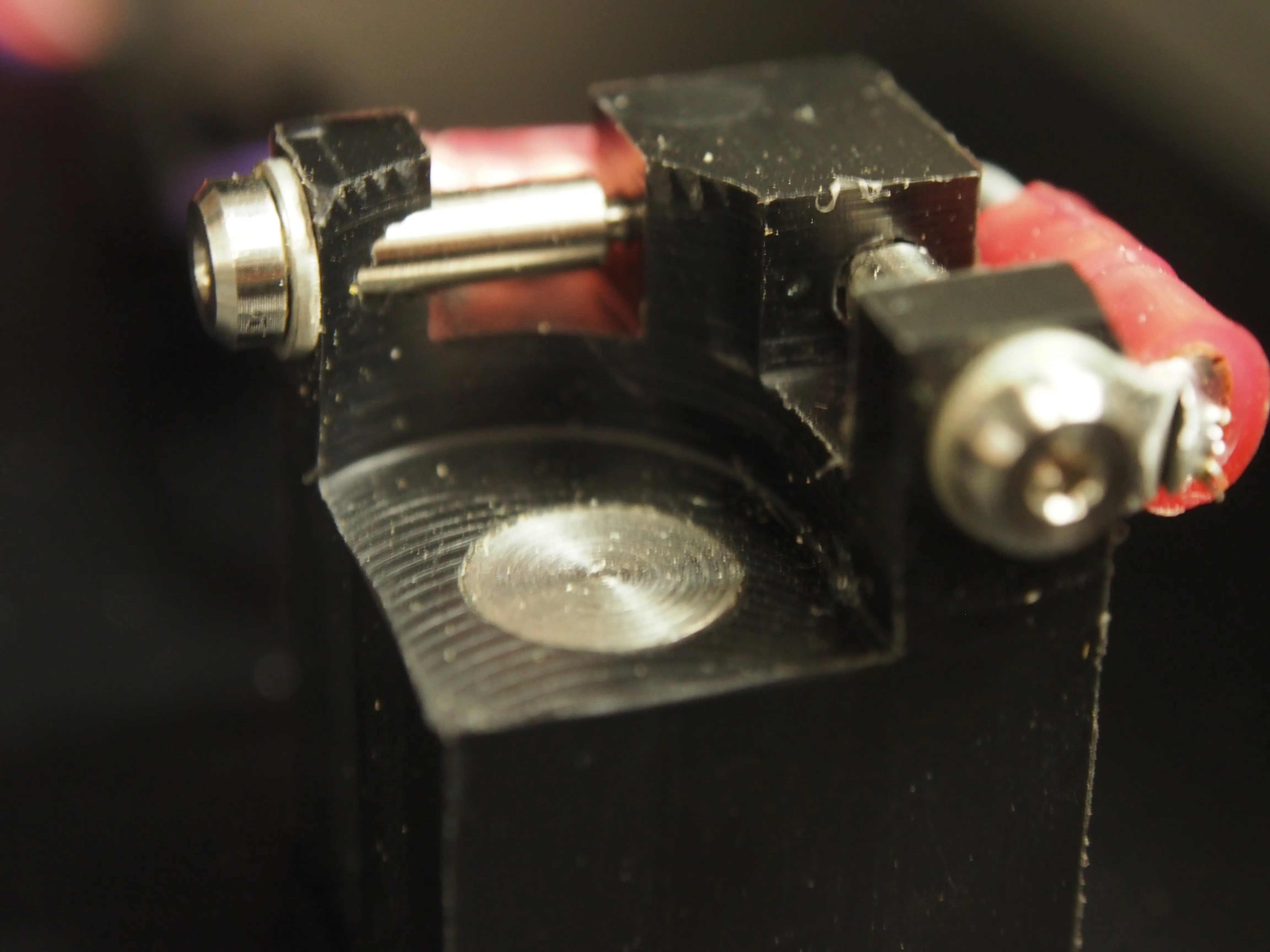

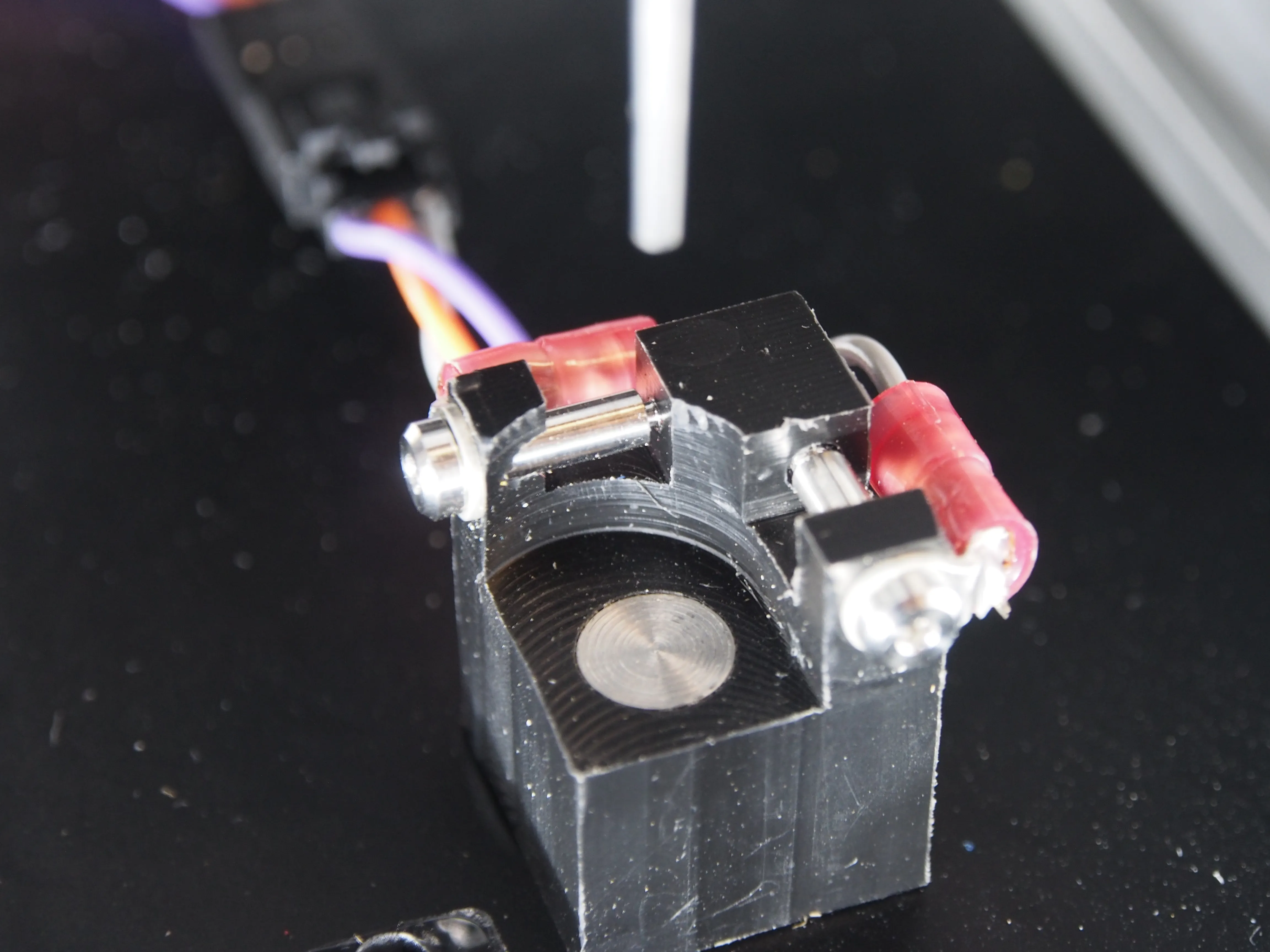

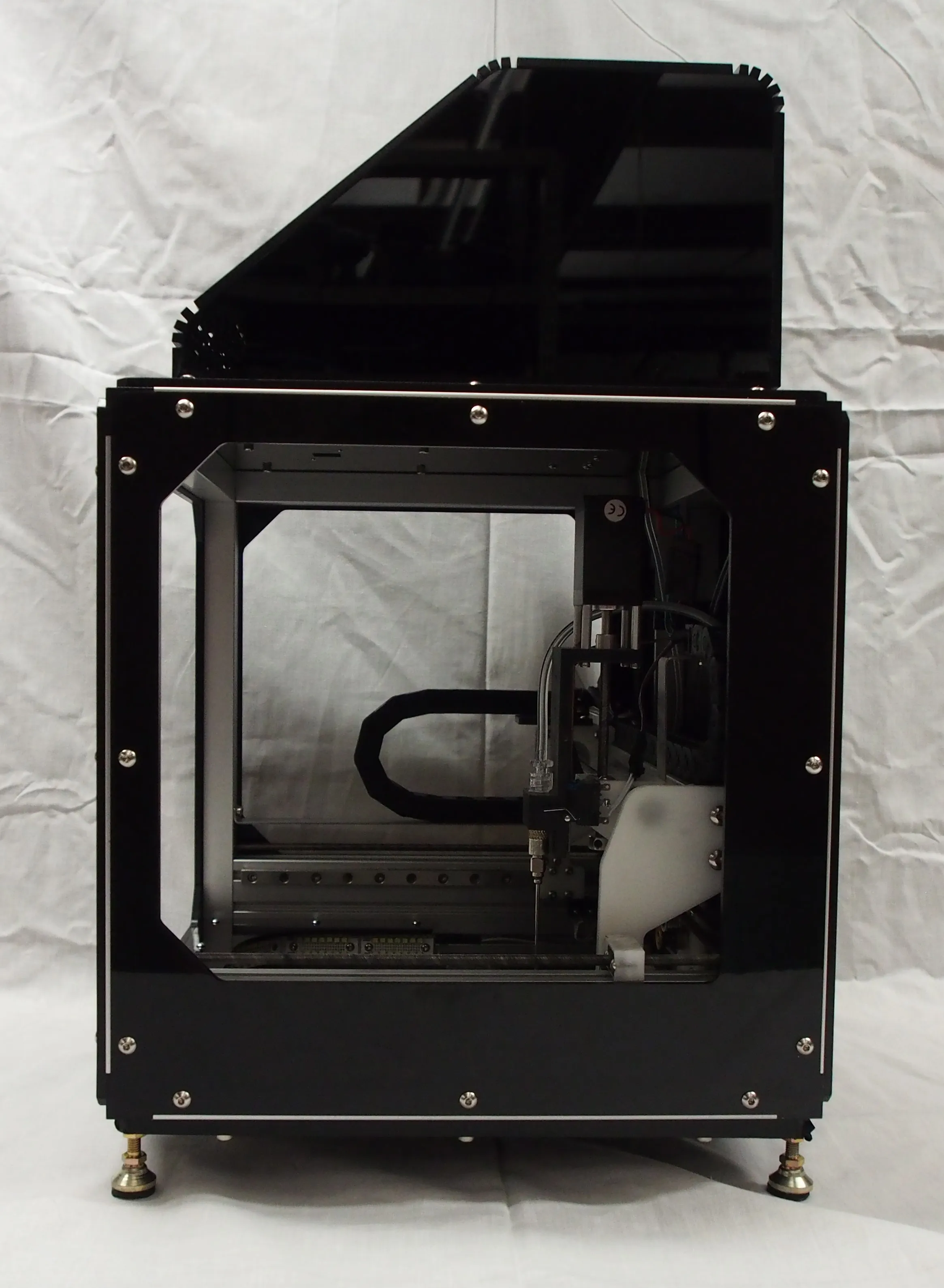

intuitive. Dylan had also created a mechanical foundation providing

repeatable alignment for a petri dish with embryos, the 96-well plate

for placement, and a waste container to get rid of extra water in our

metal pipette tip that would be used to pick up the embryos. I'd also

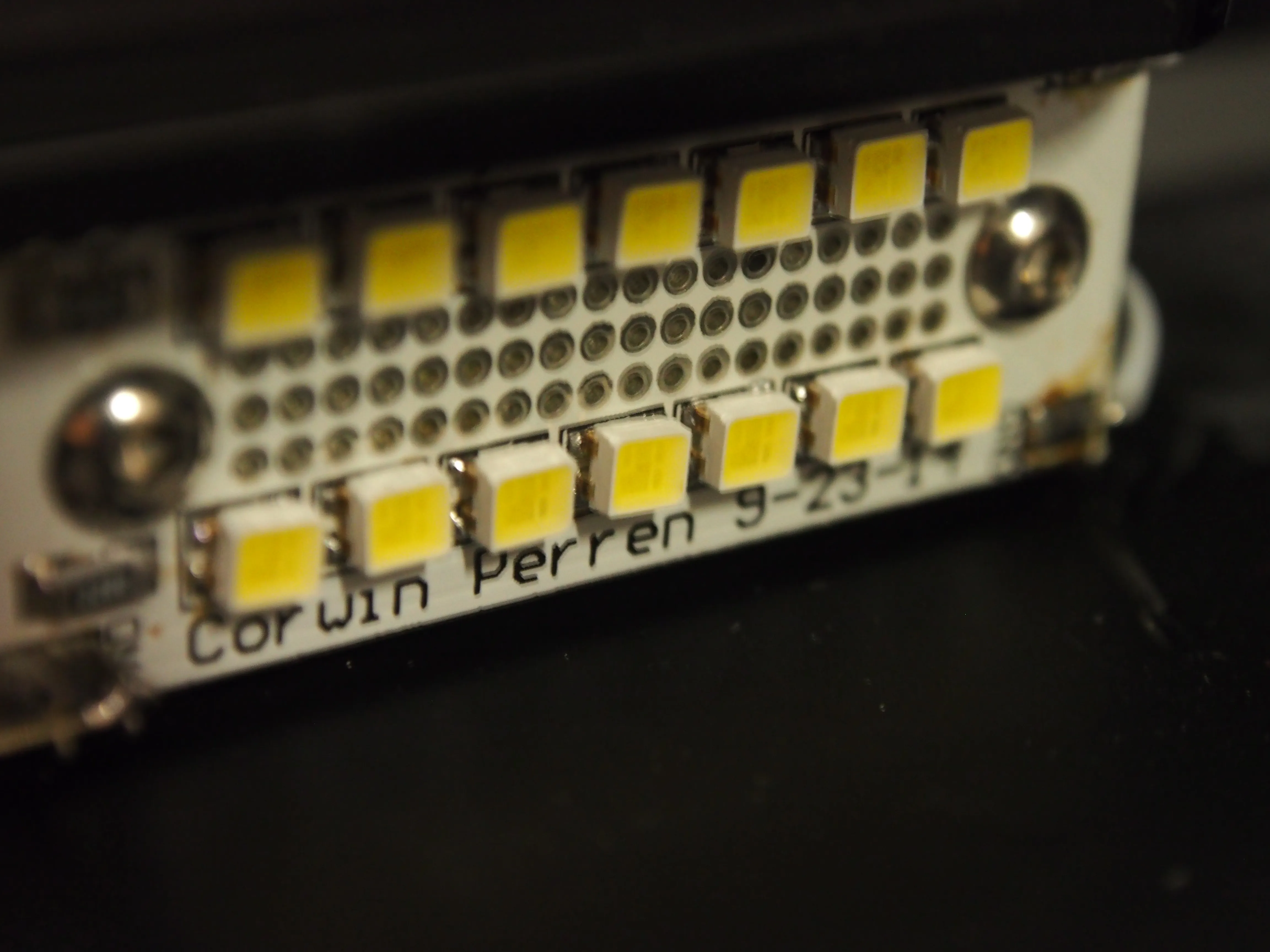

created some very bright lighting boards to mount to the unit's

extrusion, illuminating the embryos from the side, something that was

absolutely required for consistent detection with the camera. After a

long journey, we finally delivered multiple units to the lab! Seeing

such small devices performing the same task next to the behemoths which

were the prior versions was quite amusing. You could easily fit a two by

two grid of these in the working area of each of those machines.

Overall, this was a highly ambitious project, but it developed some of

my most successful skills I gained while at OSU while accelerating the

research at the lab!

Videos

Printed Circuit Boards

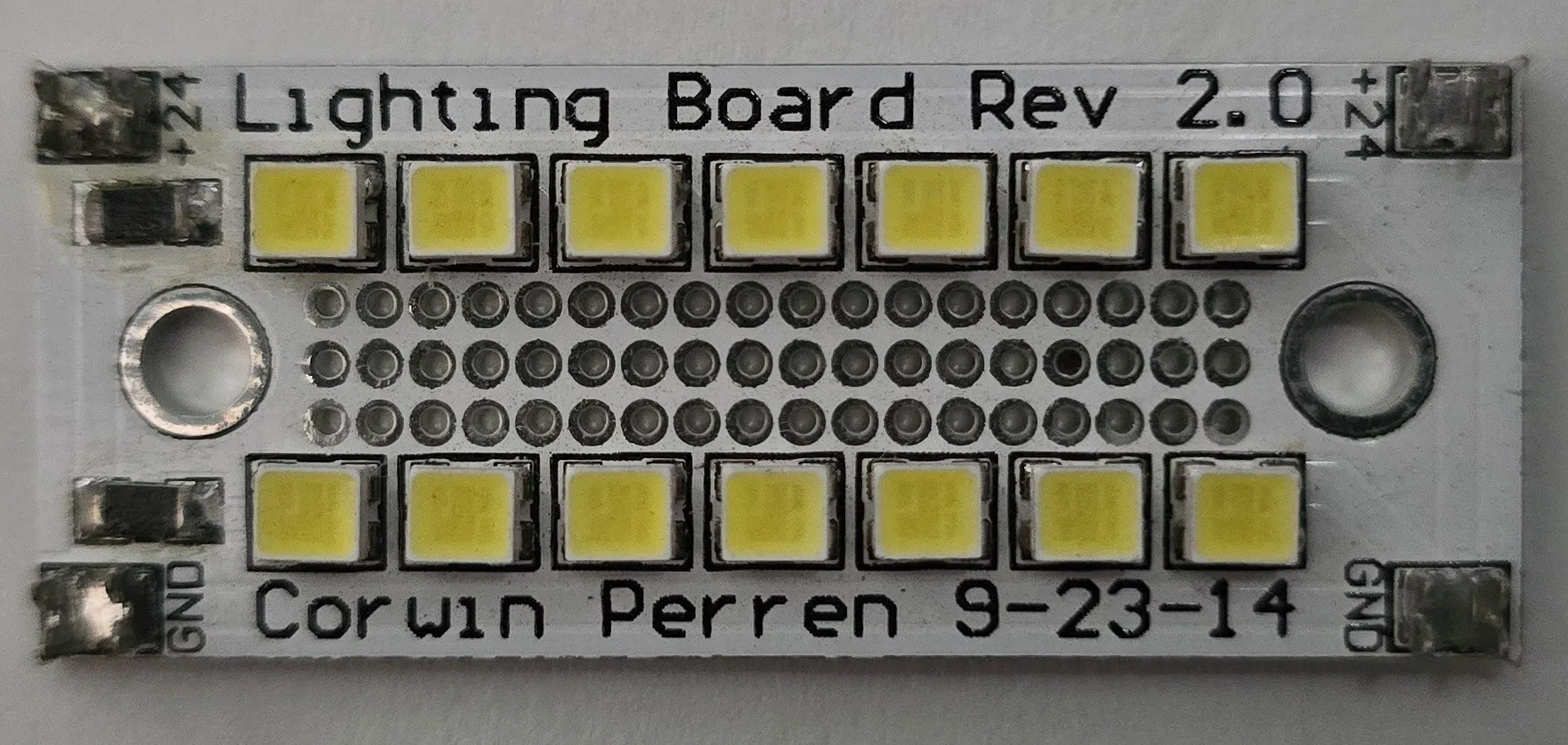

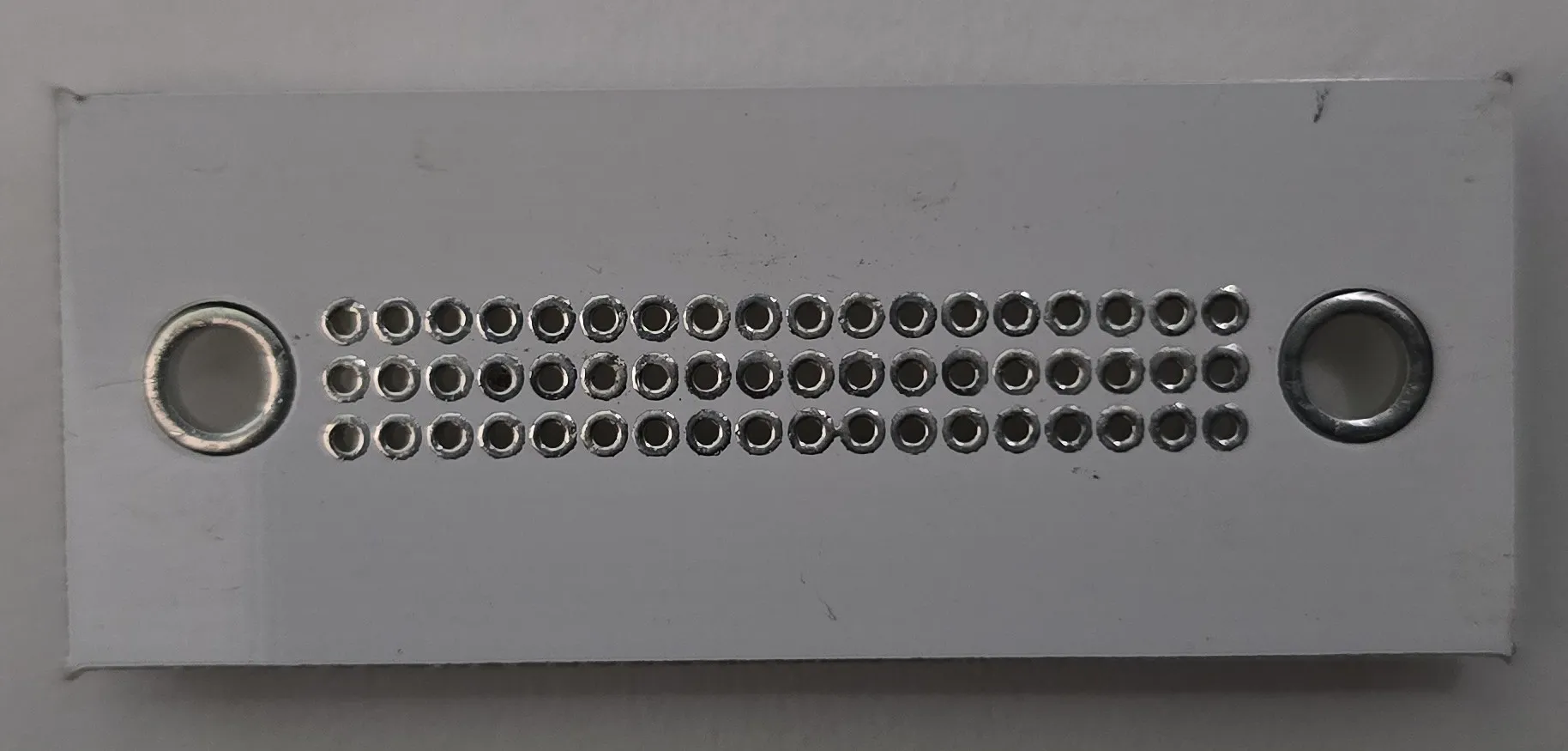

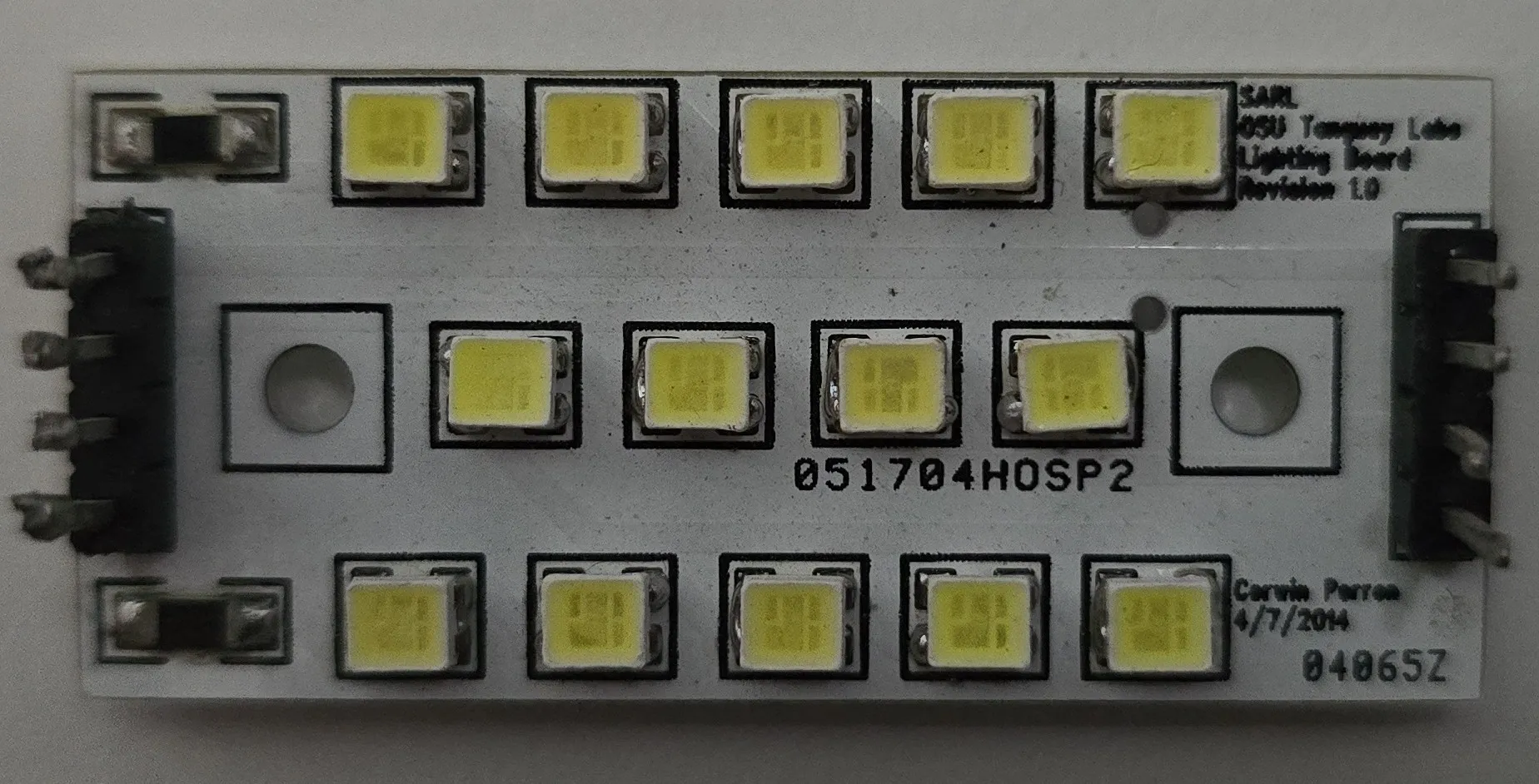

Lighting Board

Compact, bright, 24V lighting to provide high-contrast video for the pick and plate

Revision: 2.0.0

2014-09-23

- First panelized PCB design, with built-in test features

Revision: 1.0.0

2014-04-07

- Worked, but couldn't remove heat efficiently long-term

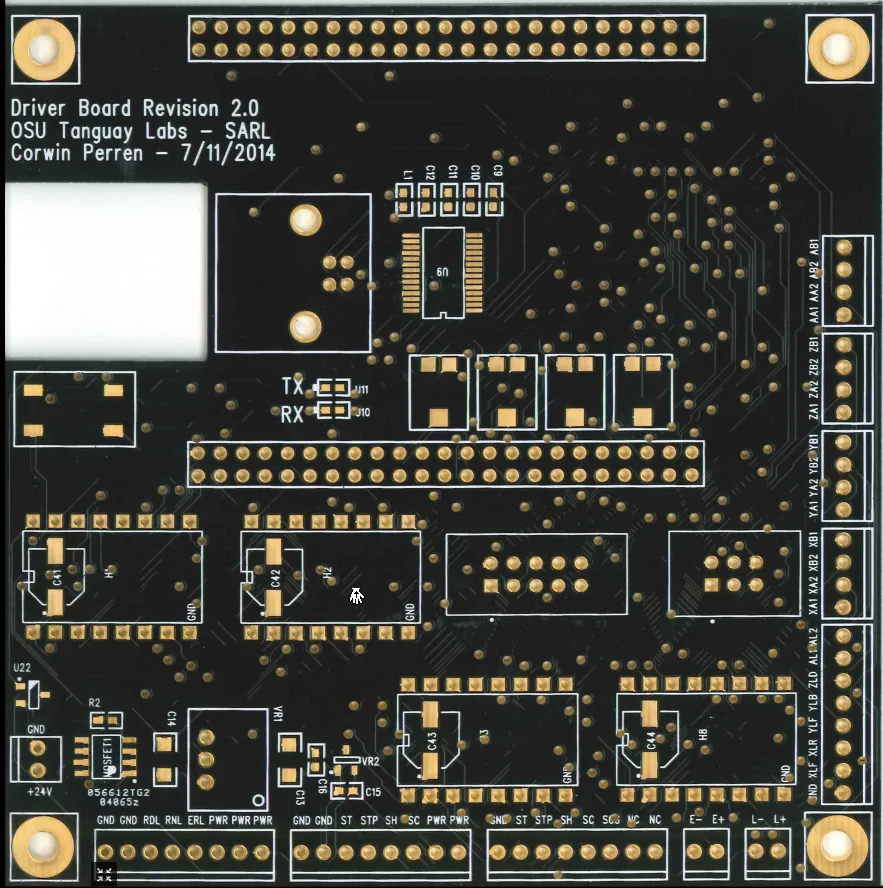

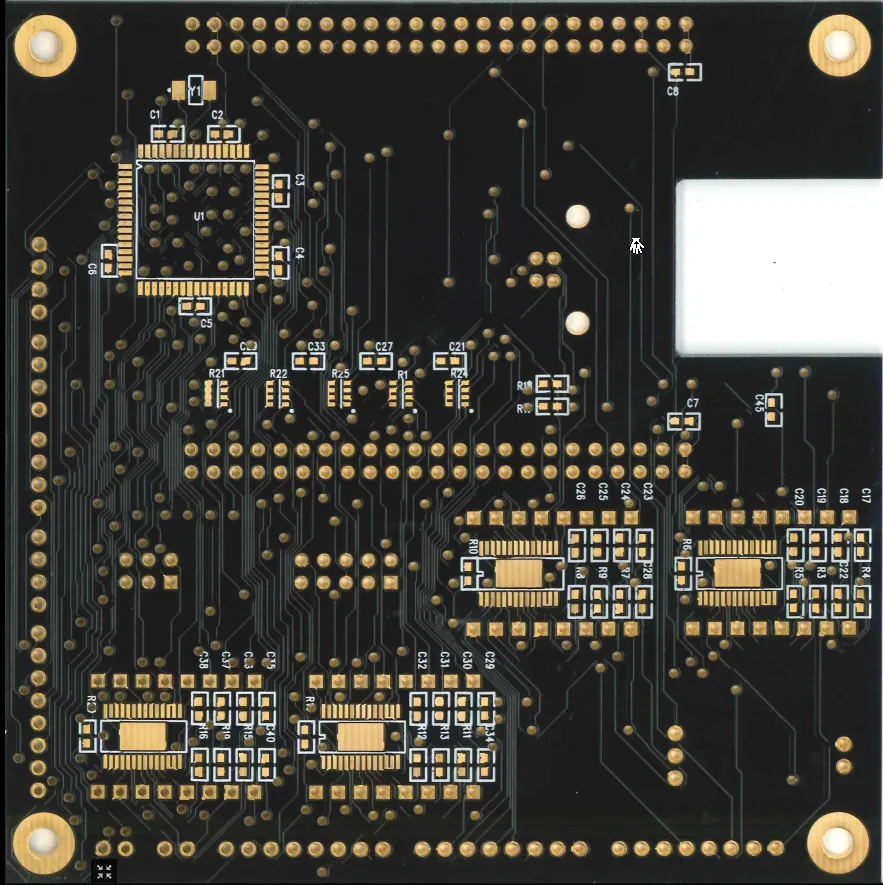

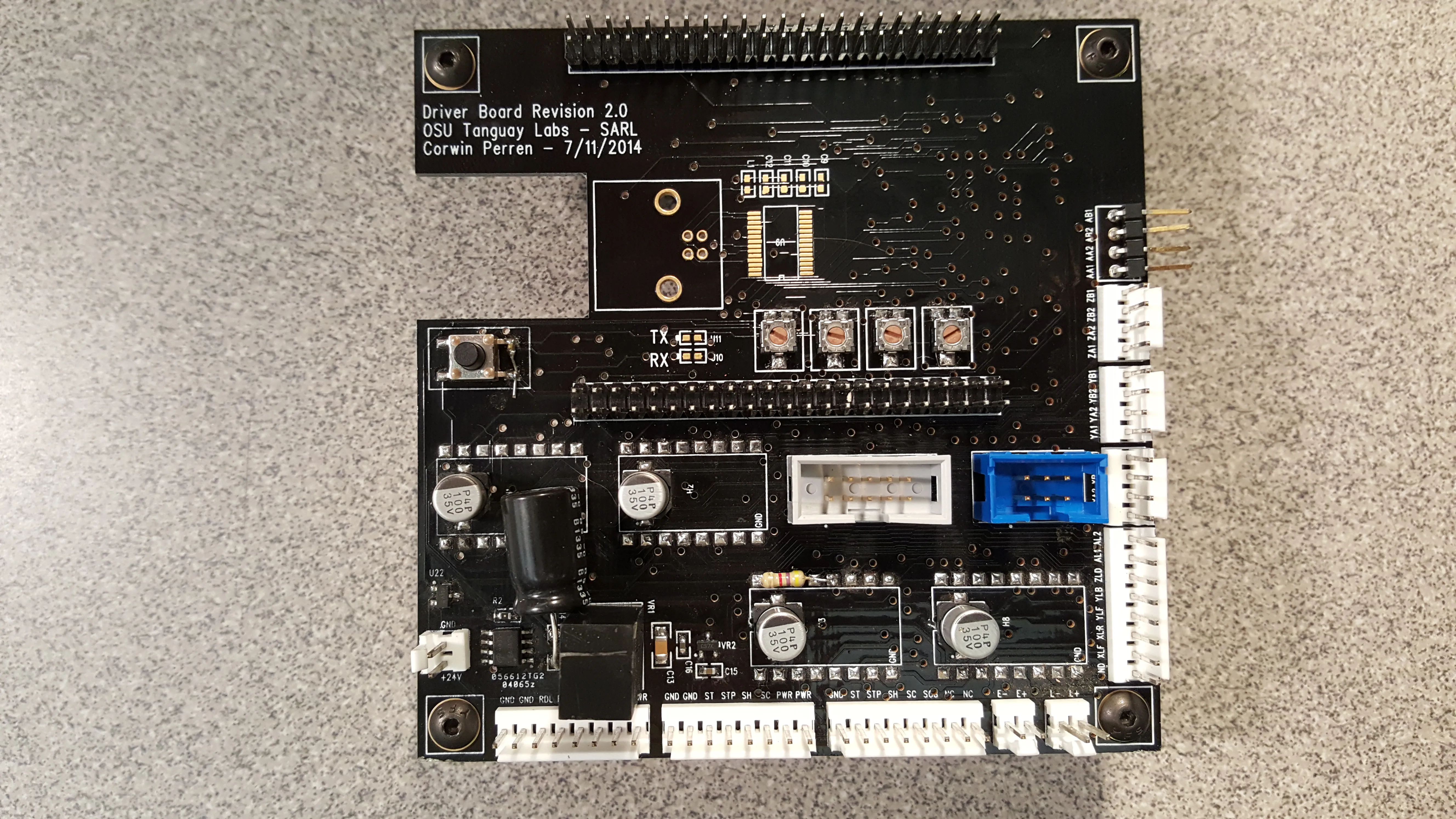

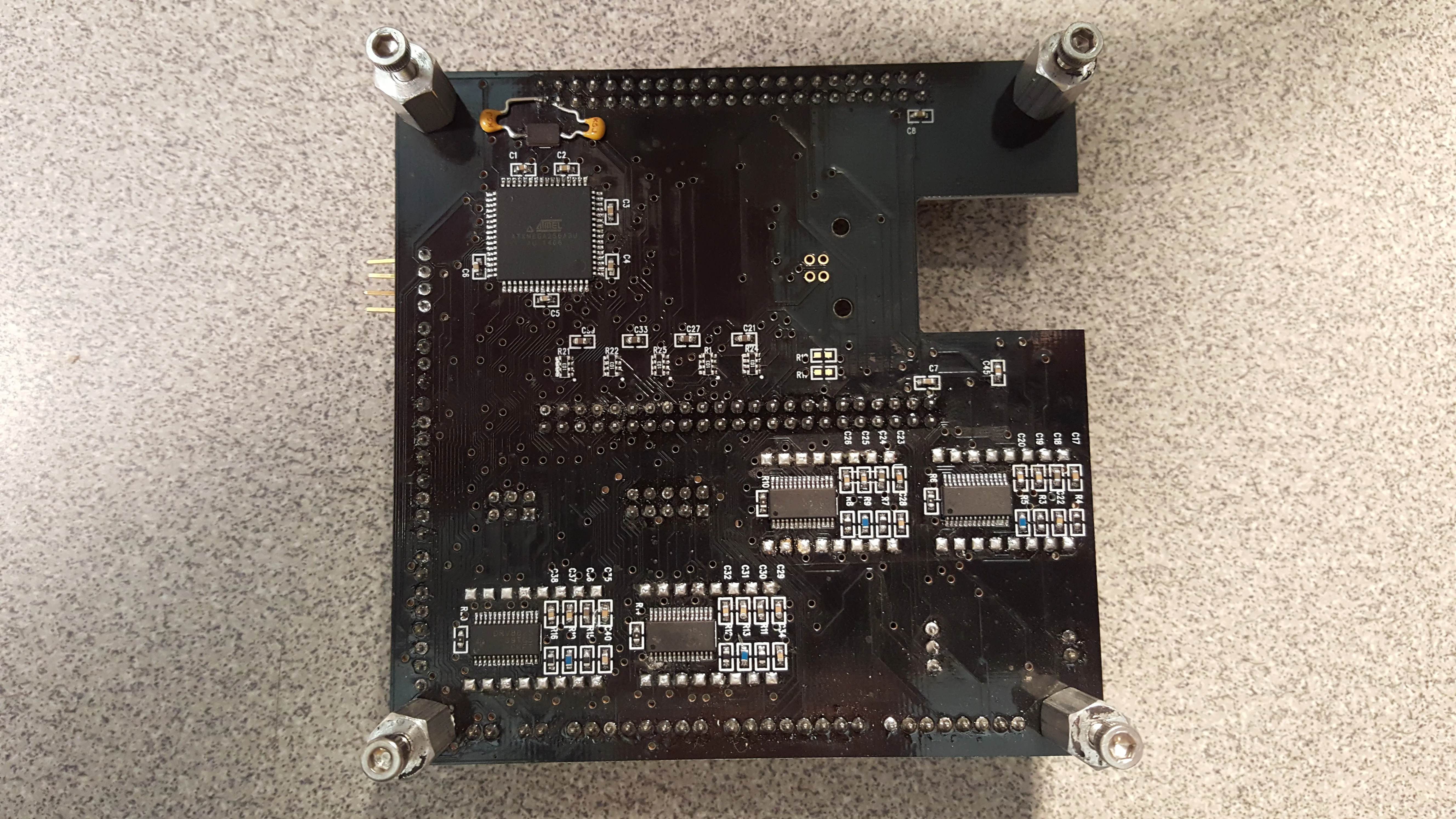

Driver Board

Motion controller, and single-board-computer interface, for the embryo pick and plate machine

Revision: 2.0.0

2014-07-11

- Functional, but ultimately scrapped due to motion control complexity

Revision: 1.0.0

2013-12-02

- First printed circuit board I ever designed, which was REALLY bad