Dechorionator

Oregon State University

College of Agricultural Sciences

Department of Environmental and Molecular Toxicology

Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory

Summary

Timeline

Started

Joined SARL Engineering

Project Started

Initial Requirements Given

PCB Released: Dechorionator

Revision: 1.1.0

PCB Released: Dechorionator

Revision: 3.0.0

Project Finished

Delivered Units to Lab

Finished

Left SARL Engineering

Key Takeaways

- Created an all-in-one tool for removing the chorions of zebrafish embryos in a controlled and repeatable manner

- Developed custom PCBs to handle motion, pump control, and user interaction

- Deployed multiple units to the lab, and one to an east-coast partner laboratory

- Cost reduced to roughly 1/5 that of the lab's previous dechorionation hardware

Relevant Skills

Electrical

- Schematic & PCB Design

- Mentor Graphics PADS

- Altium Designer

- PCB Assembly & Rework

- Handheld Soldering

- Handheld Hot-Air Reflow

- Oven Reflow

- Electrical Diagnostics

- Multimeters

- Oscilloscopes

Software & Environments

- Git

- Programming

- Low-Level Embedded C/C++ (Atmel Studio)

Details

Before delving into what was built, some quick context is probably

needed. A dechorionator is a device that removes chorions from embryos. Chorions are the outer membranes of an embryo which provide

protection, and a permeable membrane which can allow gasses and nutrients

to reach the developing animal inside. As SARL is a toxicology lab, and its

experiments need to be deterministic, this protective layer can drastically

skew tests results, and even worse, can can variances embryo to embryo, or

egg batch to egg batch. To remove this, a special protein is added to a petri-dish

full of embryos, and then the dish is gently swirled with jerking start and

stop motions. The goal is to provide light agitation between the embryo, the

dish, and their neighbors, helping the protein eat away the chorion and sluff

off into the dish. This can, and has been done by hand, but when I joined

SARL they already had two machines which which could automatically perform

this task. However, they were incredibly expensive and massively overcomplicated,

requiring a whole table's worth of custom shaker units, networked peristaltic

pumps, and servos. The engineering team was tasked with simplifying this setup

while reducing both their size and cost.

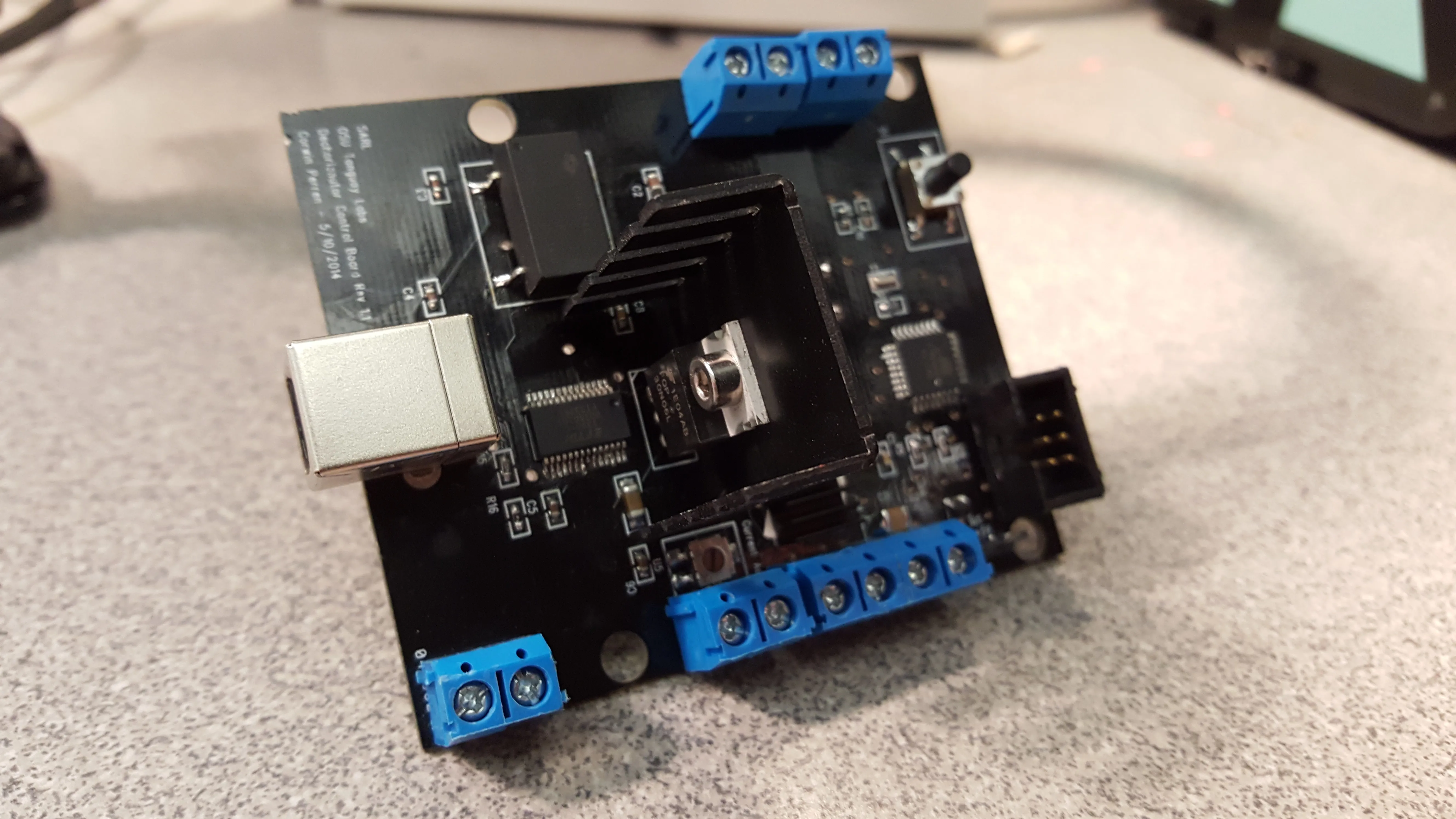

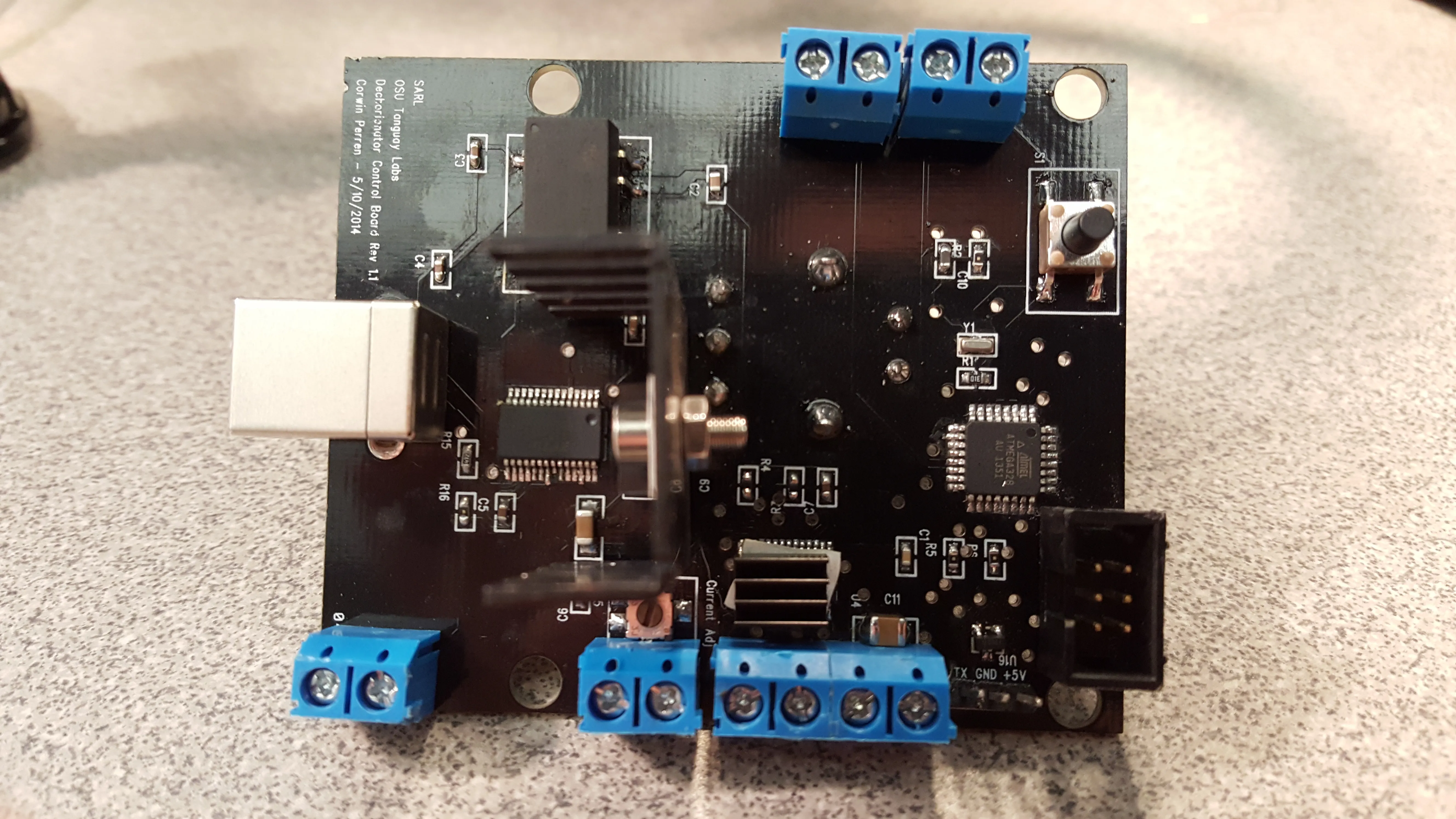

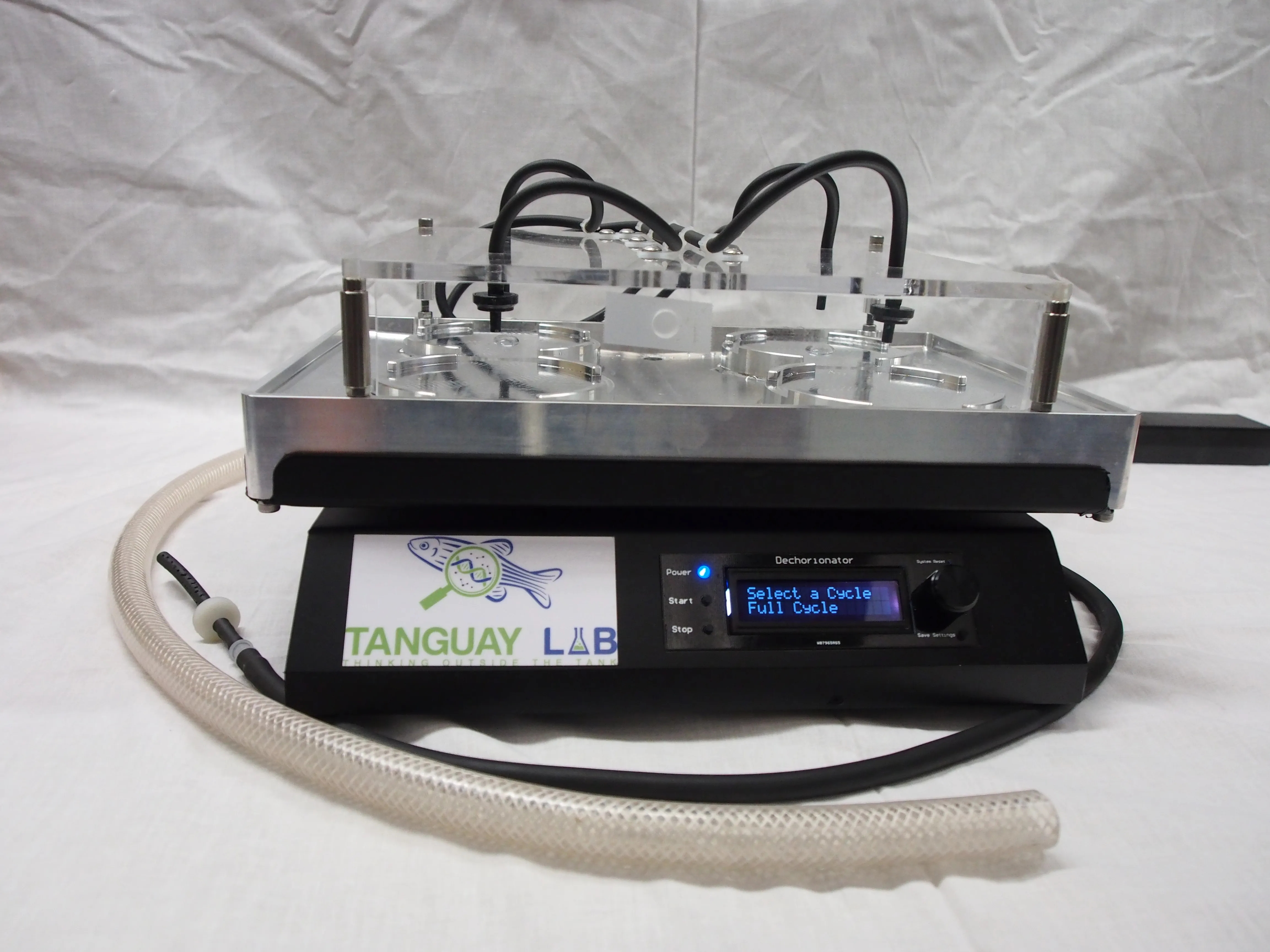

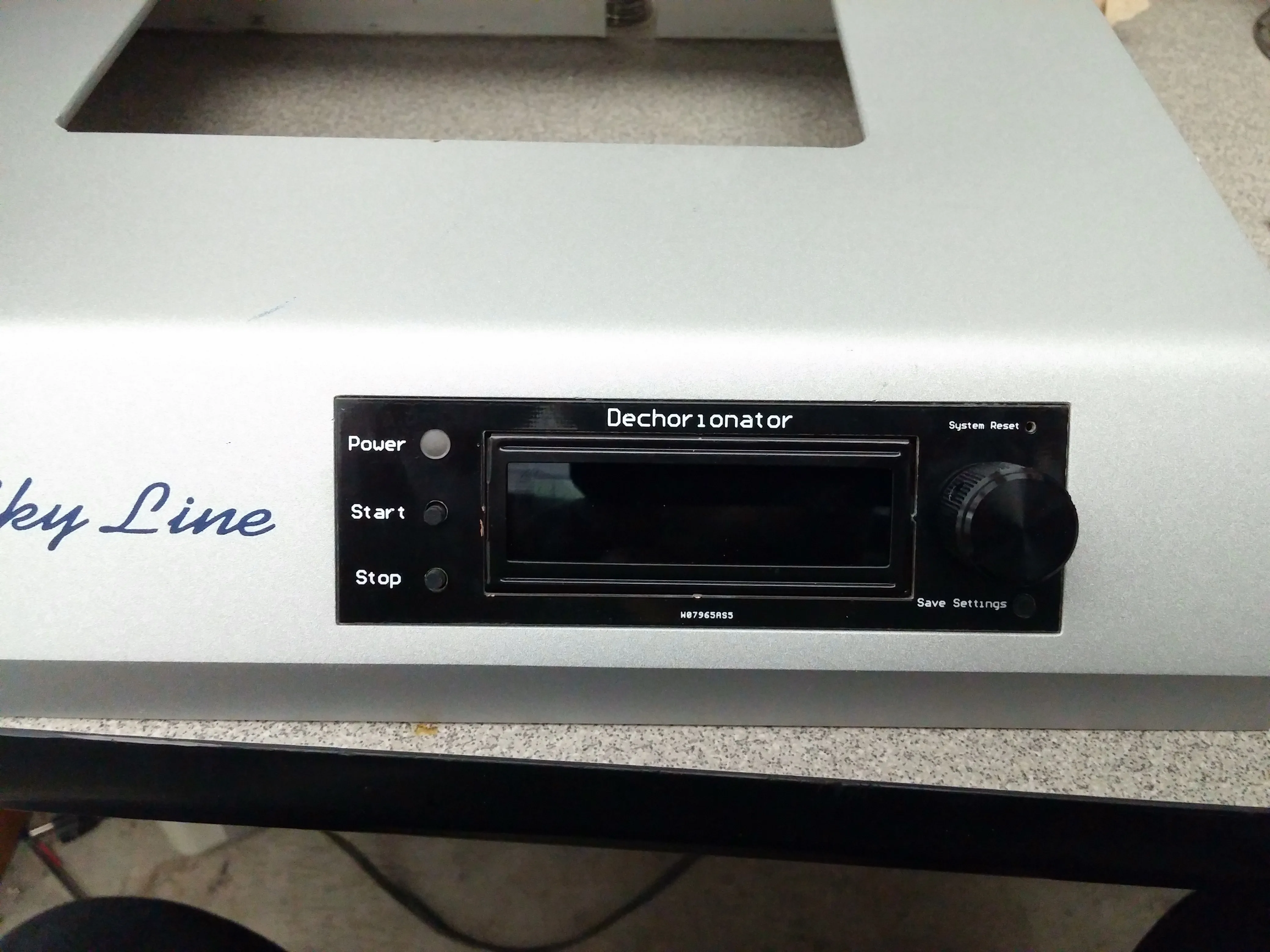

We started with a COTS shaker unit from the

company ELMI, which had a stepper-motor-based drive system, making it a perfect

candidate for easy retrofit. After gutting the existing electronics, and taking

some measurements, I started on a custom PCB design. Basic requirements were

that the board needed to be able to control the stepper motor, control the

speed of a liquid pump, provide controls to users, allow for config editing

from those controls, and provide a screen for cycle progress and editing those

config values. Since this was one of the first PCBs I'd ever designed and

hand-assembled, I started with a basic proof-of-concept which was for bench

use only (revision: 1.1.0). While I worked on the electronics, my co-worker

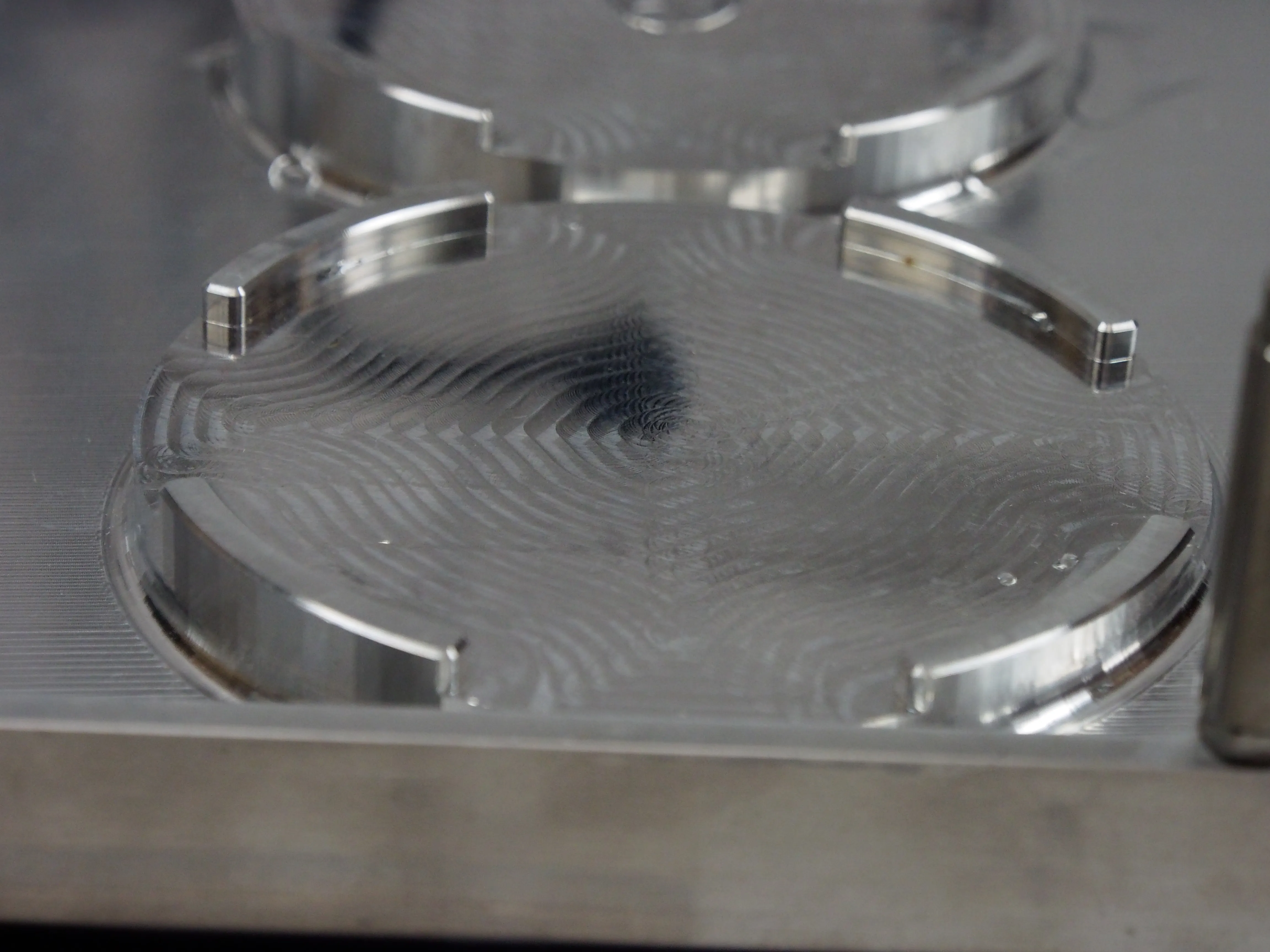

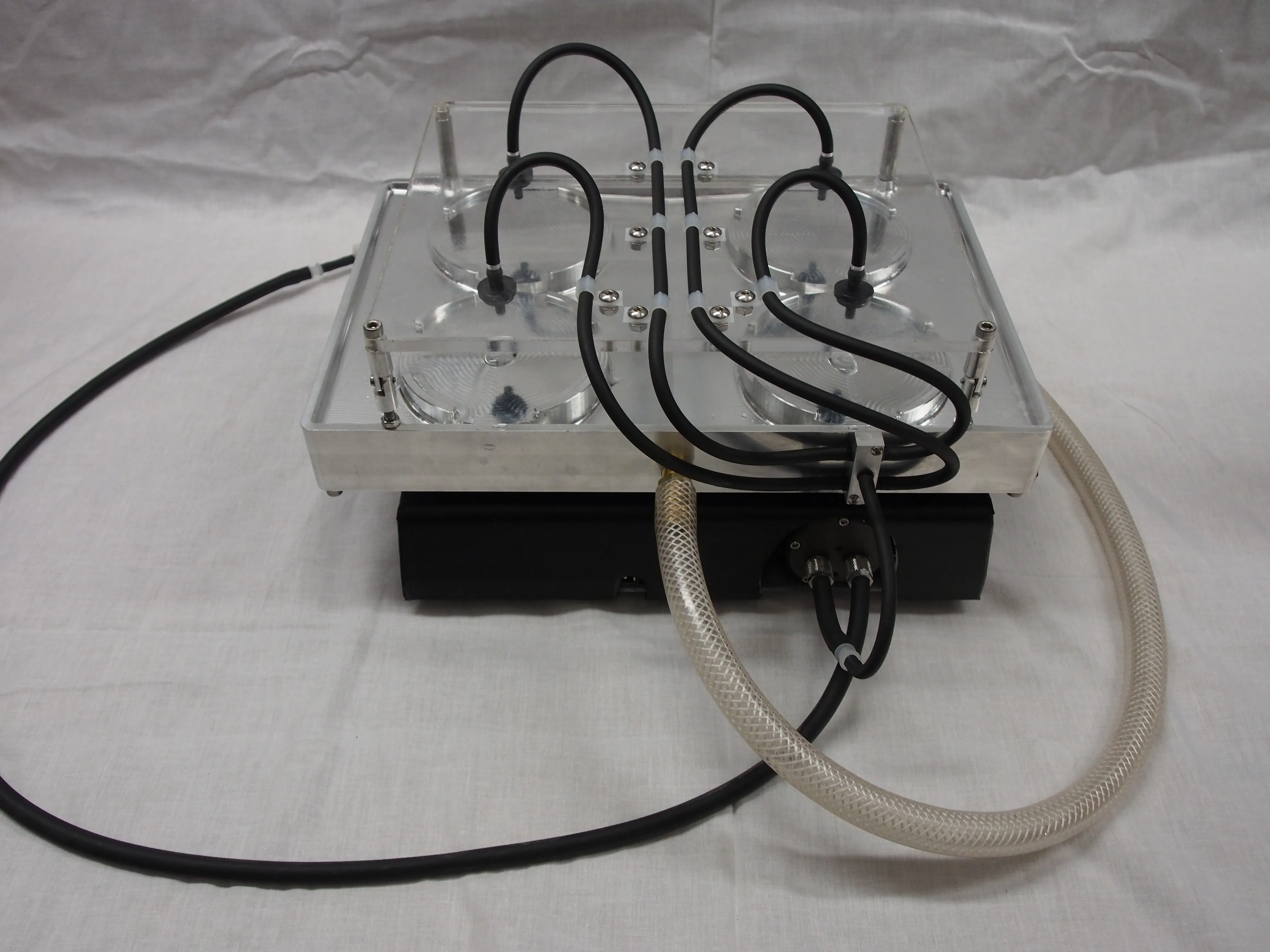

and good friend Dylan Thrush was busy designing a top-plate for the shaker to hold the dishes, shower

them with water, and drain the pumped-in liquid.

COTS

Consumer off-the-shelf

First tests showed that the overall concept was going to work, just

needing signal conditioning for the rotary encoder to avoid ghosted or

missing inputs. A larger problem we found was that the brushed-dc-motor

driven peristaltic pump was not going to be able to supply the flowrate

needed to properly shower the four dishes. We'd already chosen one of

the highest-flowrate pumps which could fit inside the shaker housing,

and ended up having to pivot to a much more expensive one from TCS

Micropumps. Luckily, not only did it solve our flowrate problem, but

also held up much better to the saltwater solution being pumped through

it than our initial choice.

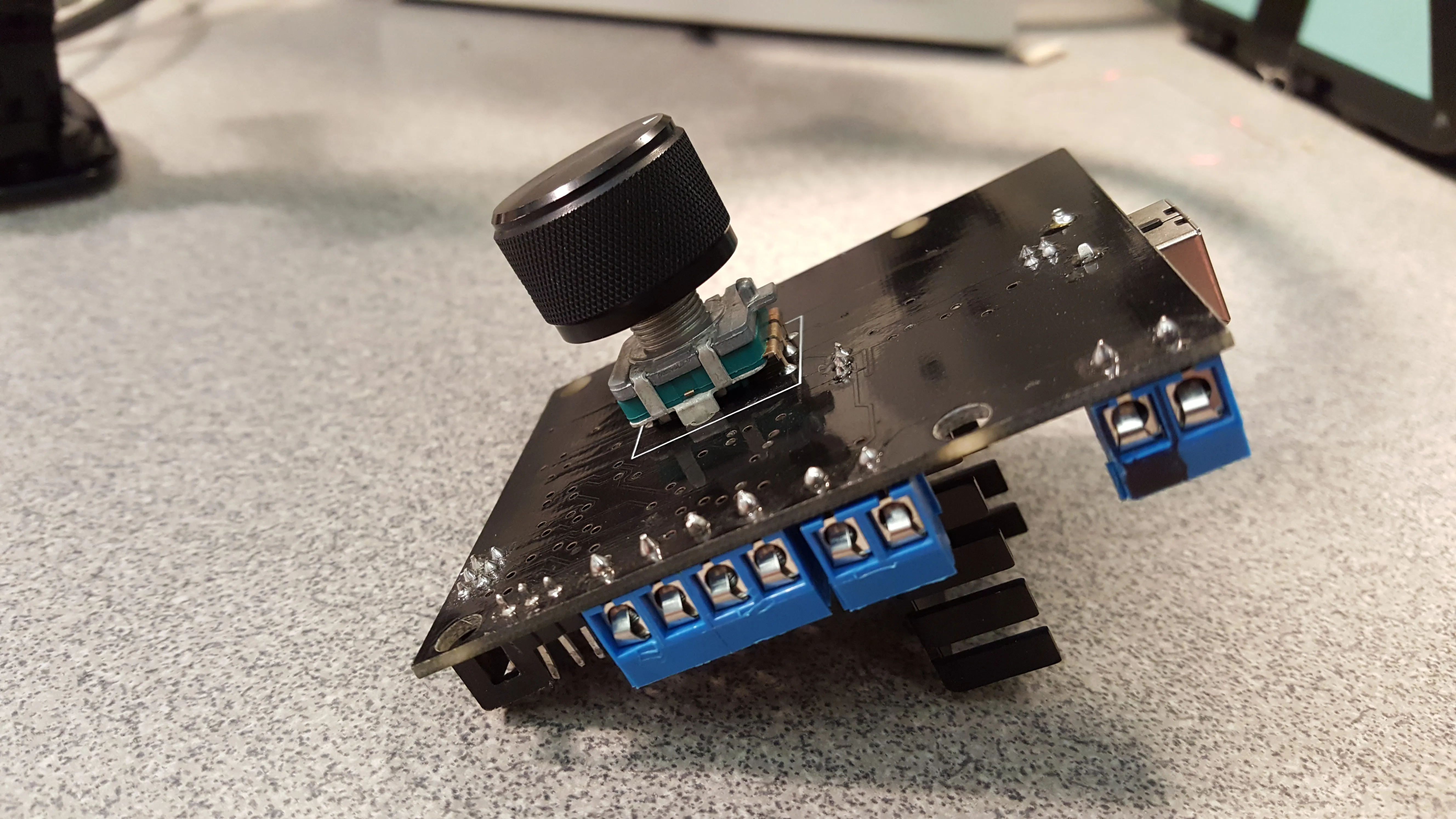

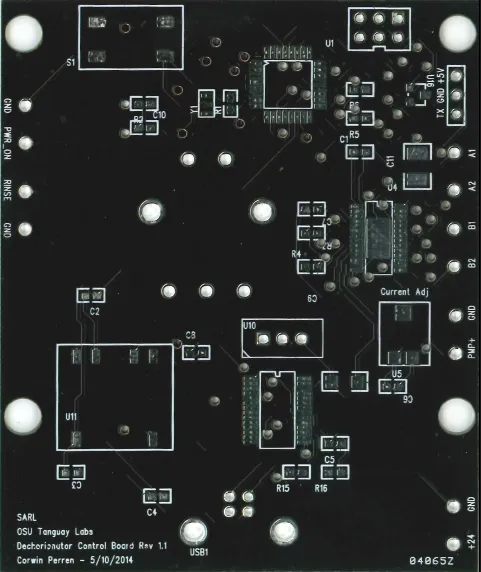

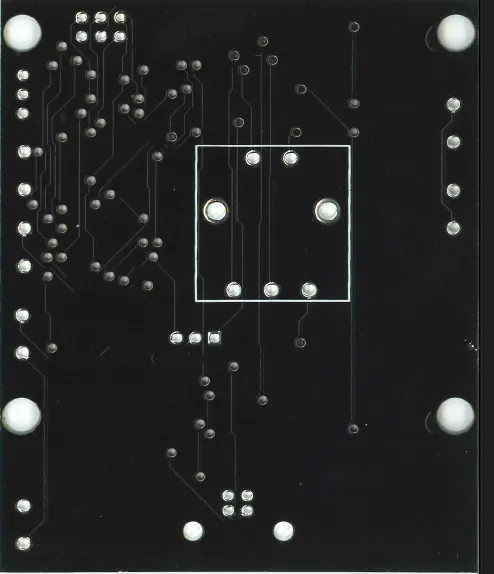

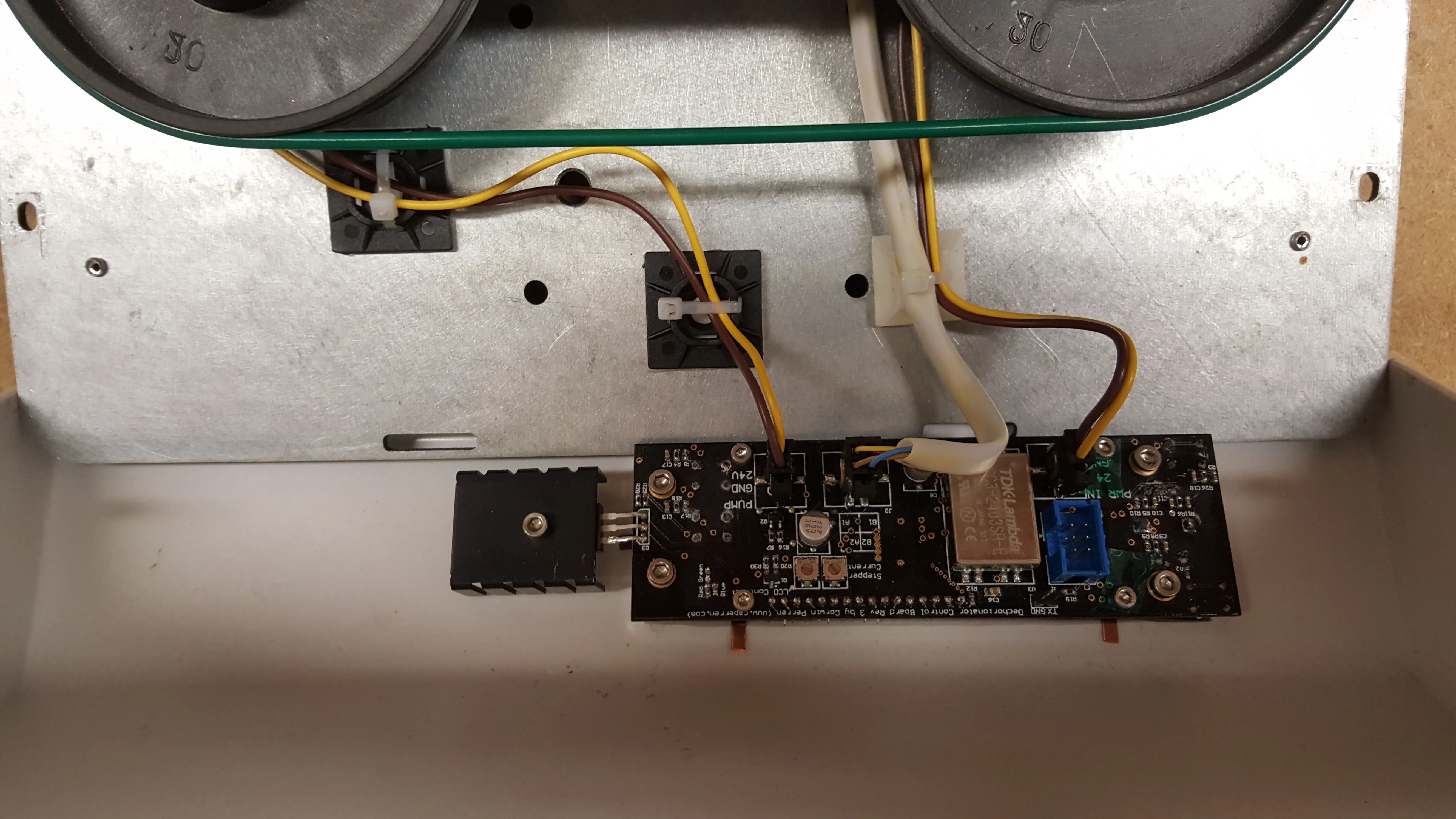

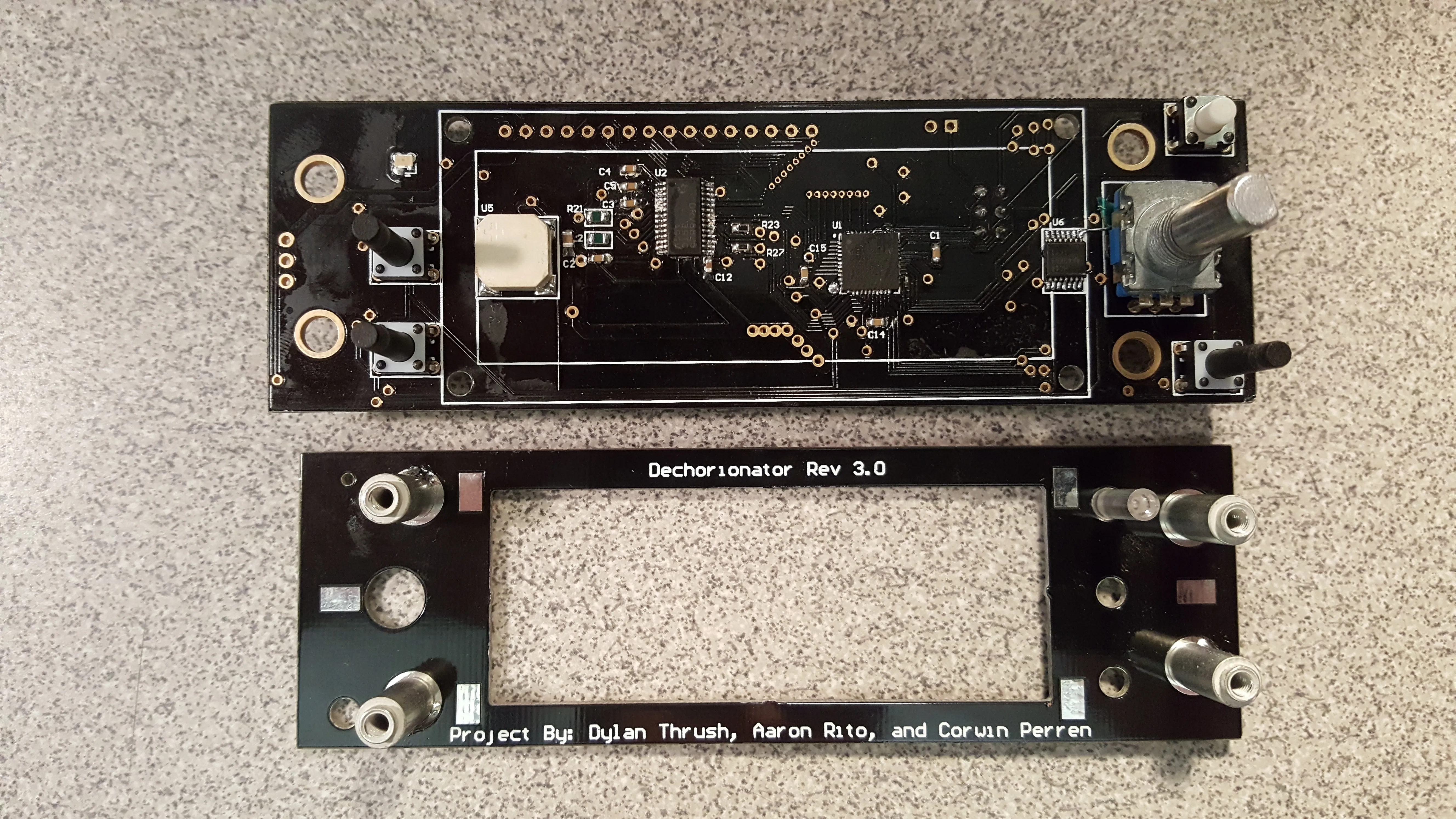

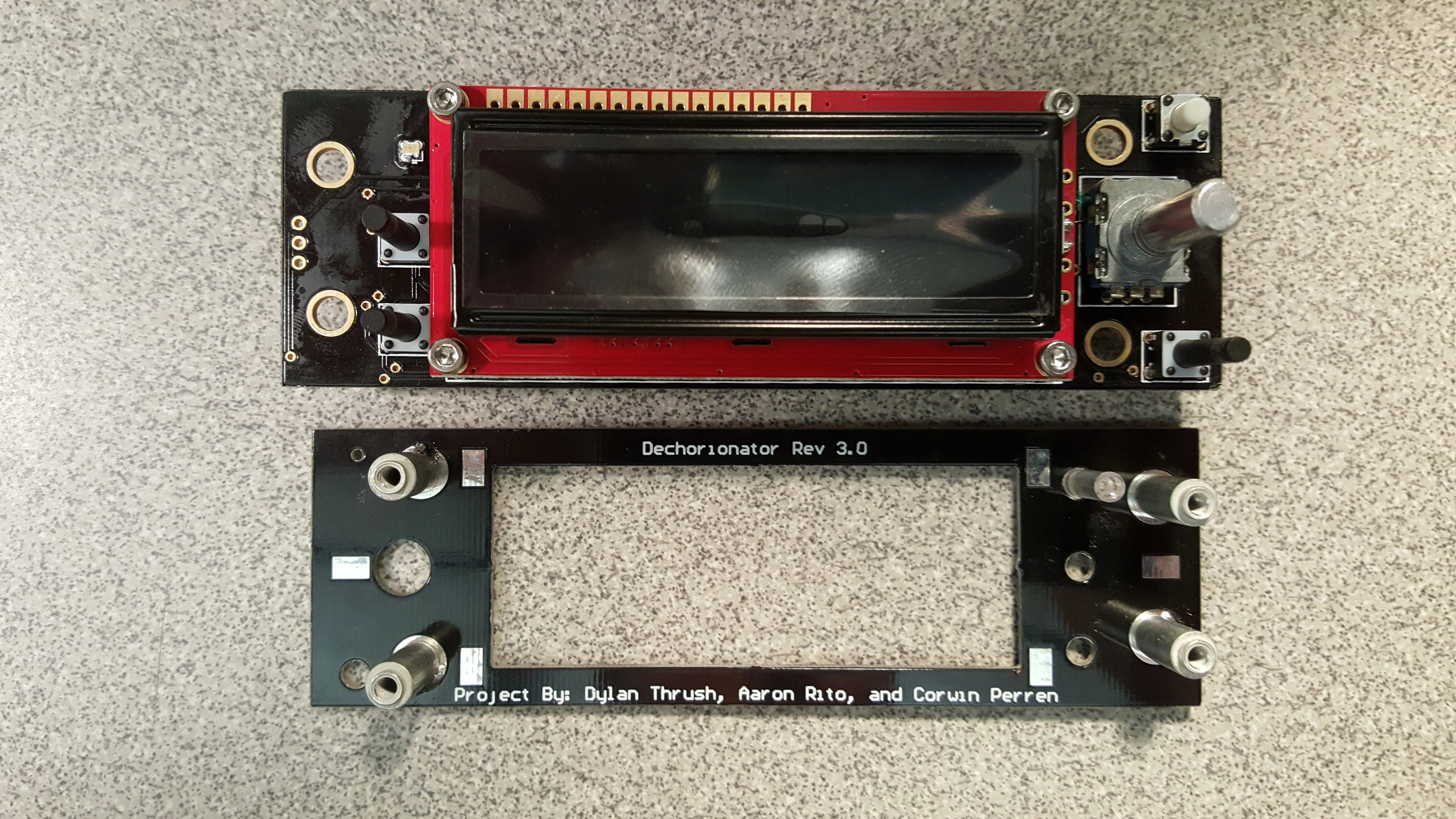

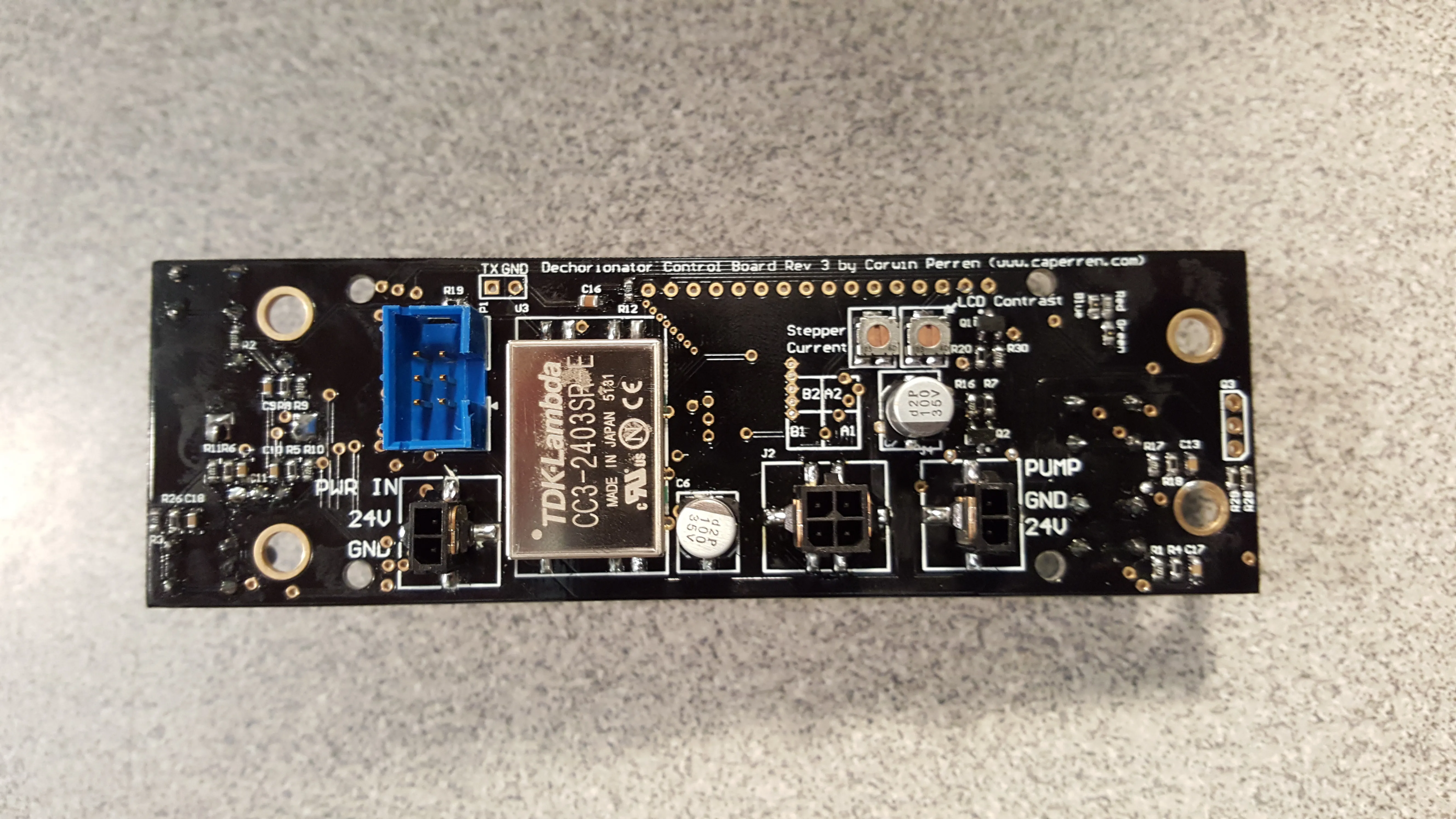

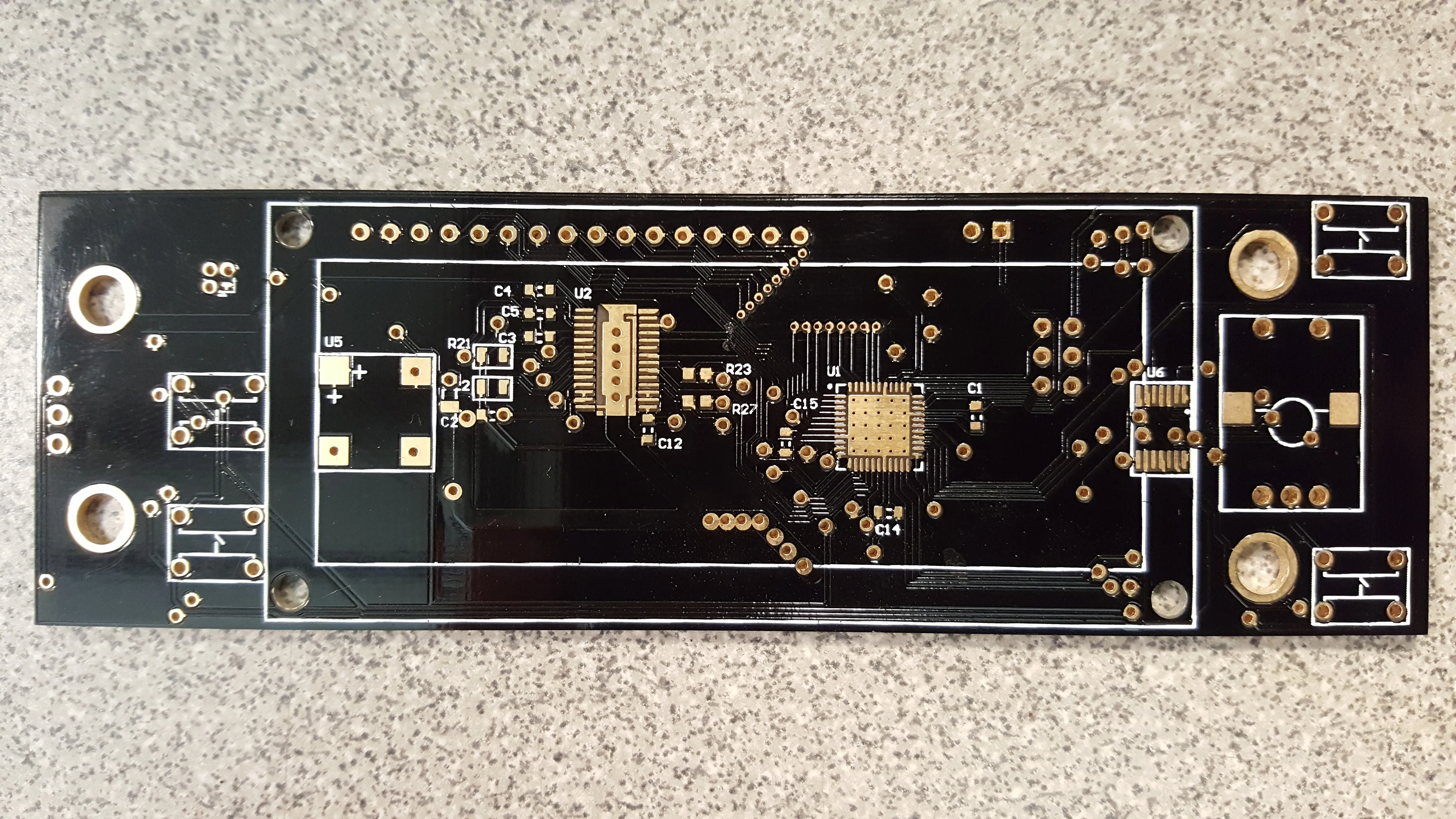

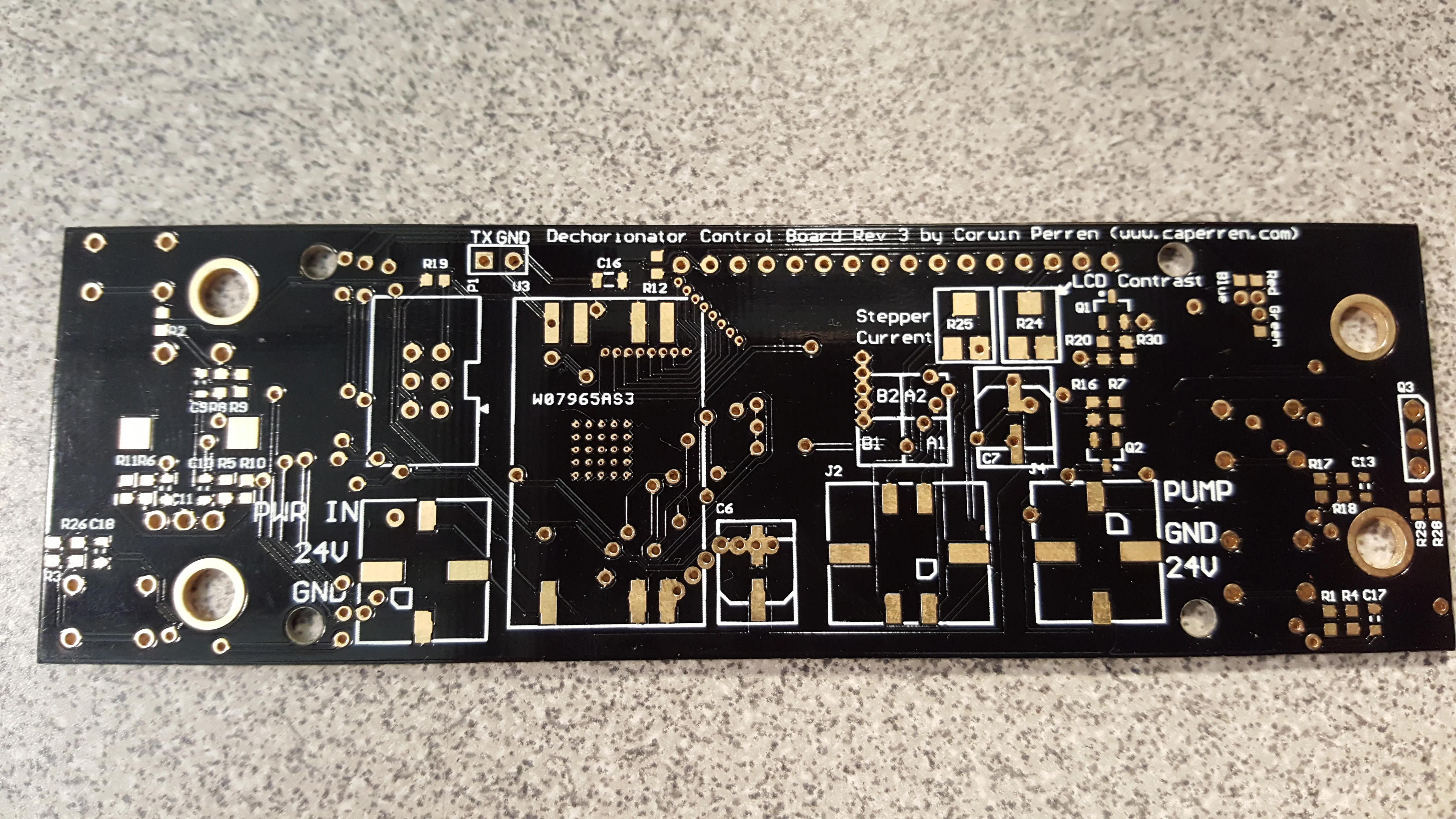

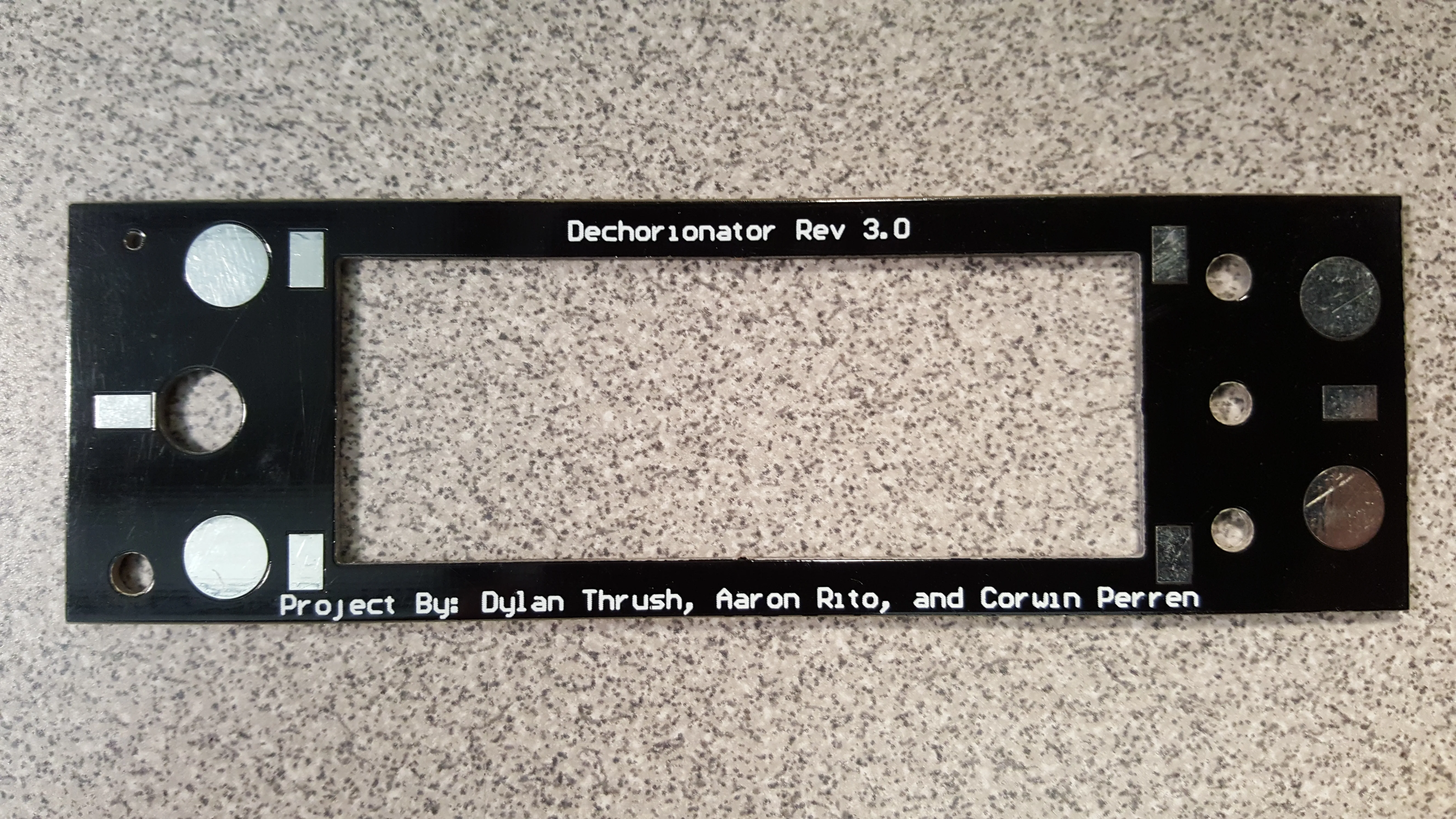

With the proof-of-concept design functional, I began a redesign of the

control PCB to replace the existing control panel and drive circuitry

from the ELMI shaker (revision: 3.0.0). The existing control circuitry

had a unique assembly design that I'd not encountered before, using a

PCB with solderable standoffs as the front panel, and soldered copper

strips as retention tabs. I was so fascinated by the design that I

decided to emulate it. Check out the images at the end of the reel above

to see how this unique assembly was put together! Around the time that

the PCBs were ready, we'd hired a new engineer, Aaron Rito, who I tasked with writing the firmware while providing input and

guidance.

Over the next few months, many revisions were made to the firmware, as

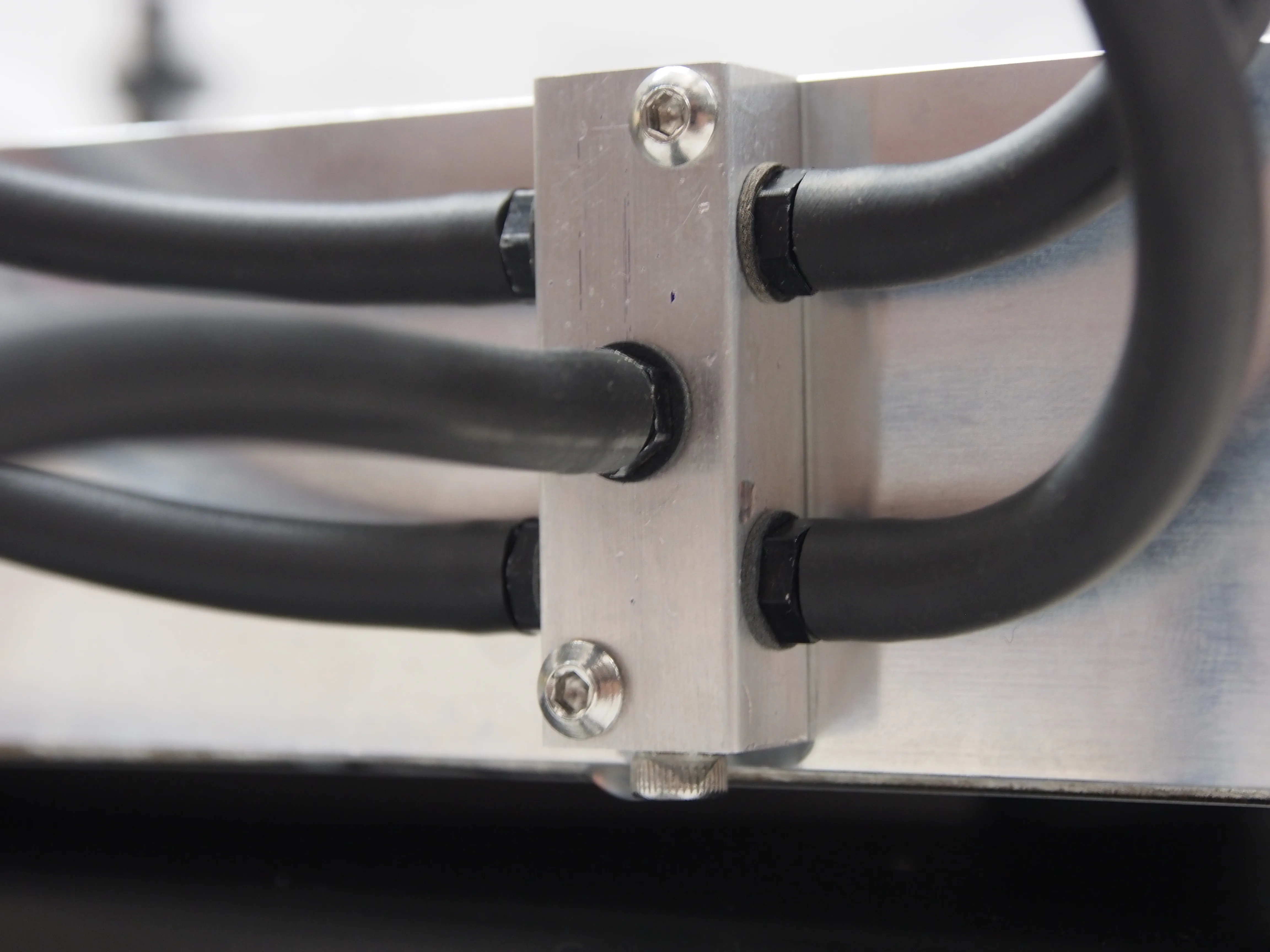

well as mechanical designs for the showerheads and water manifold. Dylan

also had a final design for the top-plate milled out that looked

beautiful. Once those changes were complete, we provided the prototype

unit to the researchers, along with documentation on how to use the

tuning values. They then spent a few weeks running the new dechorionator

alongside the old ones, while tweaking these parameters until the

performance matched. We then built up four more units, and pre-flashed

them with this configuration. Three of these went into the lab, where a

total of four of our new dechorionators sat on the same table where just

two prior-generation ones used to live. It even had additional space for

pre and post prep work on the petri-dishes! The last one I installed in

a partner lab on the east coast after flying there with the head of the

lab, Robyn Tanguay and deputy director, Lisa Truong.

Printed Circuit Boards

Dechorionator

Control board which provides motion and water flow control, along with user control and monitoring

Revision: 3.0.0

2015-08-30

Revision: 1.1.0

2014-05-10