Software Team Lead

Oregon State University

OSU Robotics Club

Mars Rover Team

Summary

Timeline

Project Started

Design Work Begins

Senior Design Presentation

Senior Design Fair

Won 1st Place!

CIRC

Project Finished

Final Documentation Complete

Key Takeaways

- Won 1st place in an international competition

- Wrote software in Python and C++ for the Rover's onboard computer

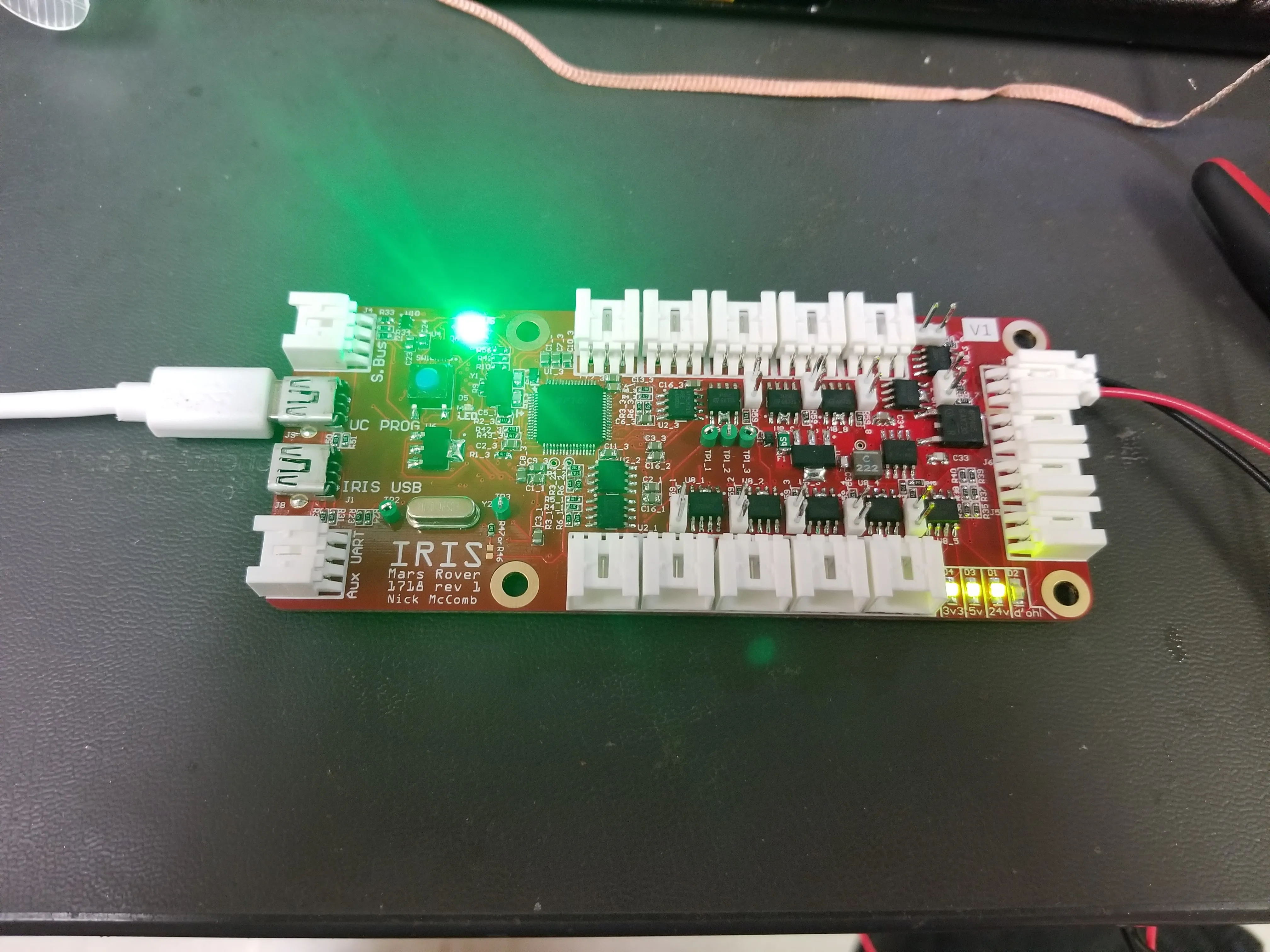

- Wrote firmware in embedded C/C++ for the Rover's distributed microcontroller sub-systems

- Hand-assembled most of the custom PCBs for the Rover's distributed microcontroller sub-systems

- Hand-fabricated much of the custom harnessing on the Rover

- Piloted the Rover during some competition events

Relevant Skills

Software & Environments

- Version Control

- Git

- Programming

- Languages

- Python 2

- C++

- Bash Shell Scripting

- High-Level Embedded C/C++ (Arduino/Teensy)

- Frameworks

- OpenCV

- Qt

- Languages

- Operating Systems

- Linux

- Ubuntu

- Linux

Electrical

- Schematic & PCB Design

- Software

- Altium Designer

- PCB Assembly & Rework

- Handheld Soldering

- Handheld Hot-Air Reflow

- Oven Reflow

- Software

- Electrical Diagnostics

- Multimeters

- Electronic Loads

- Oscilloscopes

- Logic Analyzers

- Harnessing Fabrication

- DC Power & Signal

Details

My Experience

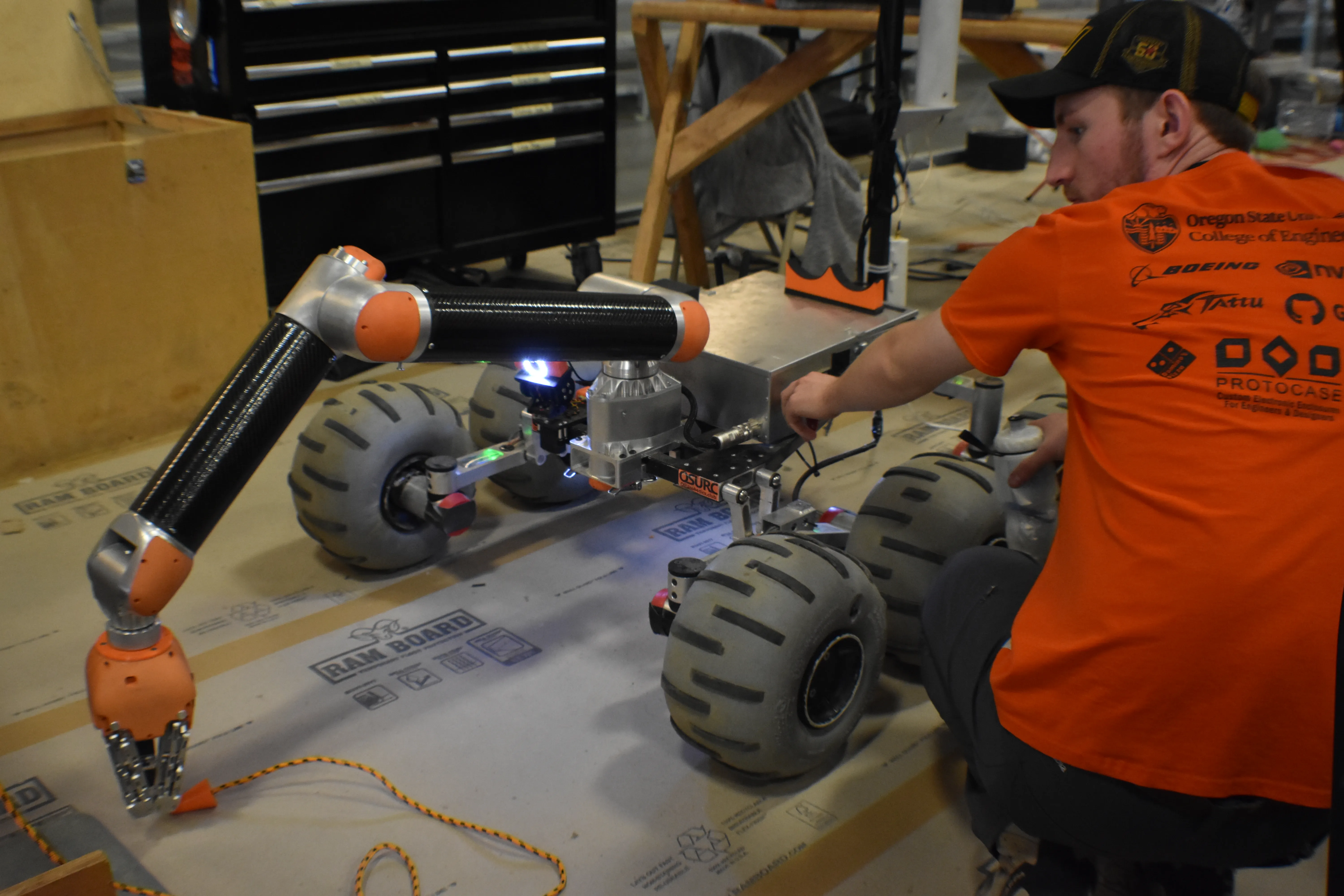

I had not originally planned to be software lead for this Rover year,

as I was already working two part time jobs and going to school

full-time, but after my best friend Nick decided to become team and

electrical lead, and my other best friend Dylan would create the

rover's arm for his senior design project, I just couldn't say no.

This also came hot off the heels of me being the emergency software

lead for Rover the previous year, writing enough code in the nine days

before competition to at least give them a fighting chance, which they

had, so I was even more prepped and ready. I only had one hard

requirement, joining as the software lead, and it was that we would

have to create a serious ground station setup. When I first joined the

robotics club in 2011, I did so because I was enraptured by the rover,

but especially its ground station, which was a full-screen display

full of stats, indicators, and buttons that got the nerd in me

excited. If I was going to go all-in, I was going to do the same, and

ended up making the ground station software my university senior

design project.

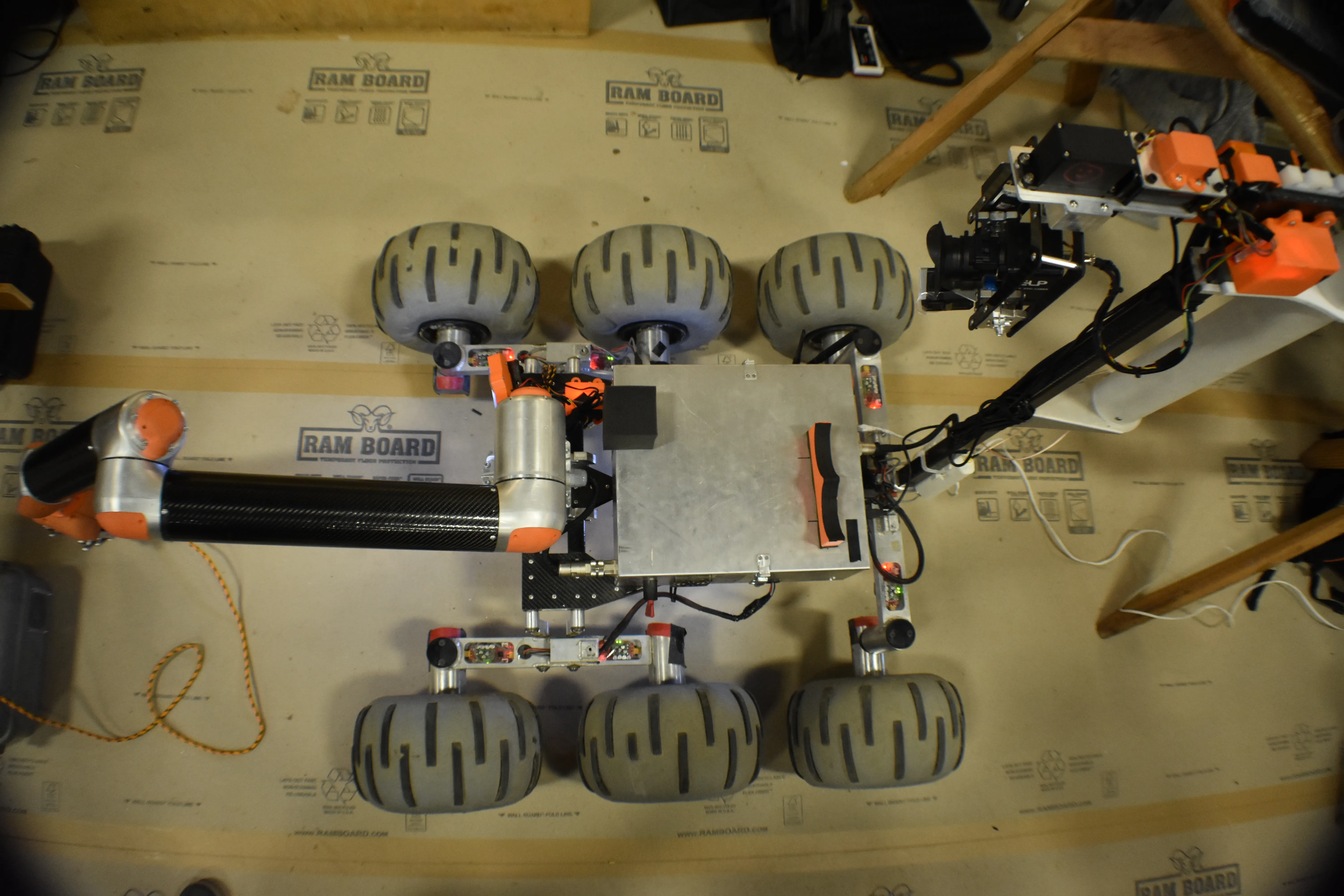

The upcoming year of work turned out to be some of the most intense I

ever had at OSU, mostly self-inflicted due to not wanting to let this

opportunity get wasted. It's worth noting, that not only was I writing

the ground station software, but also the software running on the

rover's onboard Jetson TX2 computer, all the firmware for each of the

many distributed systems, on top of also hand-assembling/debugging

most of the rover's PCBs, and creating many of its electrical wiring

harnesses. In total, I put in over 2000 hours of work on this project,

while working two part-time jobs and taking classes. It was a lot,

but, it also turned out to be my proudest achievement while at OSU, so

I'd argue it was worth it!

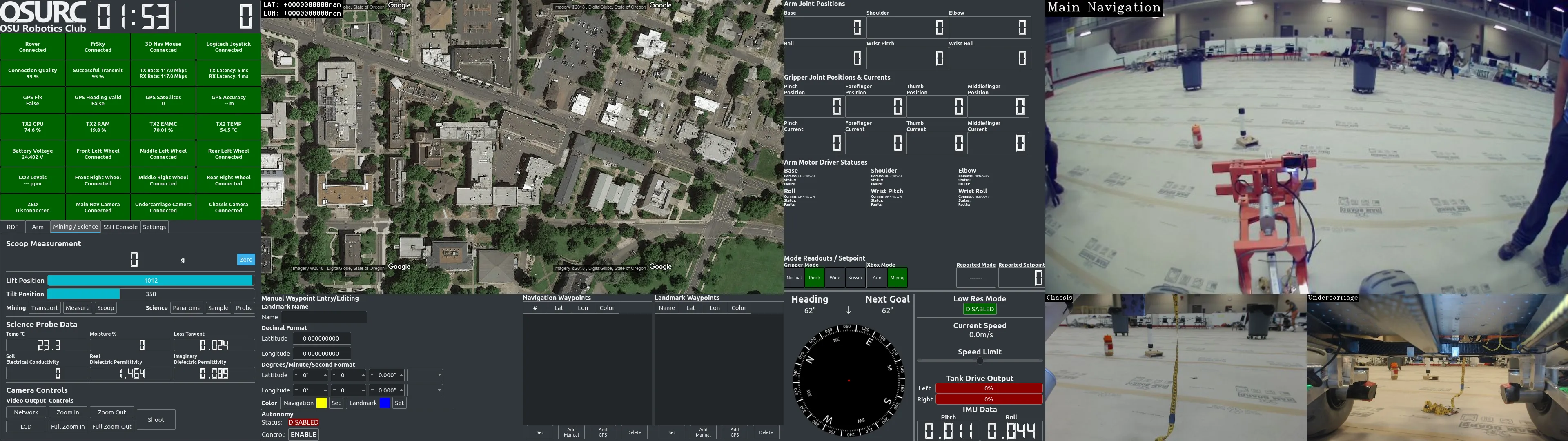

After these countless hours, what resulted was some incredibly robust

hardware and software, which didn't crash, and which allowed us to

absolutely crush the competition at the Canadian International Rover

Challenge in Drumheller, Alberta, Canada. We won first place, with a

final score of 287 points. The second best team got 159, so it wasn't

even close! On top of doing that well, the software was also feature

complete by halfway through the competition, which was no small feat

considering the amount of scope creep a project like this tends to

encounter. I was particularly proud of the ground station by this

point as well. Not only was it a treasure trove of information about

the Rover's state, but included live GPS mapping, multiple switchable

camera views with pan/tilt capabilities and quality-switching,

artificial speed limiting, and automations to automatically complete

some of the tasks from the competition with just a few button presses.

Considering the robotics team hadn't placed over 3rd since before I'd

started in 2011, finally getting a first place win was a breath of

fresh air, and made it much more cathartic when graduating the

following year.

Technical Overview

The ground station itself contained an Intel NUC with a Core i5, 16GB

ram, nvme ssd, and was connected to two 23″ 1080p monitors. I chose

two so we would be able to see all primary Rover systems without

having to swap between tabs or pages, which I’d had to do on some

other software I’d written and knew wouldn’t be efficient when we were

in the middle of a timed event. The desktop ran Ubuntu 16.04 with the

ROS2 stack. For the UI, PyQt was used, allowing for easy tweaking

using QtCreator, and which provided access to QtSignals, a feature

that made simple cross-thread communication much easier in Python. The

Python code itself was Python 2, which was a limitation of the ROS2

stack. Control of the rover was done via USB xbox controllers, plus a

keyboard and mouse.

The Rover itself ran on an NVidia Jetson TX2 single-board computer

powered from a 500Wh li-on battery. The electronics box also contained

a fuse box, power cutoff, network switch, battery backup, composite to

network video converter, usb hub, FrSky controller receiver, and

custom usb->RS485 adapter board. The TX2 ran Ubuntu 16.04 with the

ROS2 stack, just like the ground station. All remote control boards on

the Rover were communicated to using the modbus protocol over RS485.

Interfacing with the arm was achieved via RS485 as well, but using the

custom simplemotion control library provided by the motor controller

company. Using linux UDEV rules, usb->serial and cameras were

symlinked to custom, repeatable names at /dev/rover/name so that

devices could be accessed identically after reboots. Custom ROS nodes

were written for each system to be controlled, and the whole Rover ROS

package set to start automatically at boot. The Rover could be

controlled with an FrSky X9D controller whether the ground station was

running or not. The controller could also override all other control

inputs on-the-fly by flipping a switch on the controller. This was a

safety feature to ensure runaway ground station or autonomy code

wouldn’t allow the Rover to take off on its own. Conversely, the Rover

would also work without the controller powered on, but would

immediately allow for this override if turned on at any time.

Communication with the ground station was done using two Ubiquiti

Rocket M2 long-range wifi radios, along with their 10dB

omnidirectional antennas. This simple setup allowed for a transparent

ethernet link to be made between the two systems, allowing for useful

features such as remote debugging and code upload. The radios were

tested to work at roughly a kilometer away, when mostly line-of-sight.